Like the endless stream of lousy paintings sold at garage sales, or the ceaseless arguments for why climate change isn’t real, the supposed principles and rules of food and wine pairing are nothing more than bad art or junk science. Holding food and wine pairings up as the apotheosis of the gustatory experience does far more harm than good — both to consumers and to the wine industry — because it turns wine from something universally simple and essential into something special and specialized that requires knowledge and skill to fully appreciate.

And that, my friends, is a sham of epic proportions.

Enjoying wine with dinner has been one of humanity’s greatest pleasures since forever. So how in the world did it end up being a source of panic attacks and the fodder for hundreds of books and scores of useless smartphone apps?

A Modern Malaise

Once upon a time, before technology, travel, and trade shrank the world into a single global marketplace, people sat down to a meal and poured themselves a glass of wine that they had likely purchased from a neighbor or made themselves. For the vast majority of wine’s 6000 year history, people drank what was grown nearby.

We tend to forget that making wines from different individual grape varieties and the sheer diversity of wines that creates is itself an incredibly modern phenomenon. With notable exceptions such as Burgundy, until recently most wines were field blends of whatever happened to be traditionally planted in the region. To put a finer point on it, before the late 20th century, the only wine pairing option for most of humanity was either the “local red” or the “local white.”

Sure, the rich, the royal, or anyone running an empire of some sort or another had the leisure and luxury of shipping wines to themselves from around the globe, but most ordinary people didn’t start facing anything resembling a dilemma of what to drink with what they eat until the last 60 years or so.

The modern explosion of global trade came quickly on the heels of replanting most of the world’s vineyards, which had been wiped out by the phylloxera epidemic at the turn of the 20th century. These two factors, combined with improvements in winemaking technology (the advent of cultured yeasts, temperature-controlled vats, and drip irrigation, among others), drove an explosion in both the variety and availability of wines from every corner of the earth that has continued for the last 50 years.

Not long after World War II, instead of just “the usual stuff,” for the first time, wine drinkers around the globe had access to wines they never would have seen before.

Two Types of Wine Cultures

As much as we talk about the blurring distinction between the so-called “Old World” and “New World” of wine, there still lies some truth at the heart of the distinction. There are two types of nations in the world. Those that have a long history of traditional, local wine growing, and those who do not.

In countries like Italy and Spain, the idea of needing a book or an app or more than a moment’s thought to decide what wine to pair with your meal seems downright strange to most. If you want to know what to drink with your food in places like that, just look at the wine lists, even in these modern times. Go to an everyday restaurant in Alba, Italy, and you’ll be drinking Barolo and Barbaresco. Go to one in Logroño, Spain, and you’ll be drinking Rioja.

It’s only in places that don’t have these traditional cultures of wine that you begin to see a focus on and concern over what is the right thing to drink in a given situation.

“I think that where you have an endemic wine culture, people are not so reverential about wine, it’s just an everyday thing,” says Anne Kriebehl, a German-born, London-based Master of Wine. “The idea that wine is snobbish and elitist is frankly an Anglo-Saxon idea.”

The Paradox of Choice

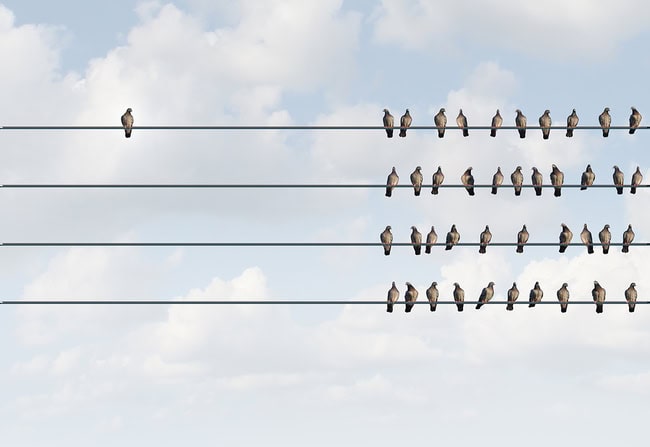

Especially as Americans, with a native alcohol culture more focused on beer and spirits, no simple regional intuition exists for what wine we should drink with our food. Instead, we’re faced with the seemingly endless aisle of wine capable of bewildering anyone who doesn’t already have a specific bottle in mind.

Experiments have proven fairly conclusively that this is a real problem.

“All this choice has two negative effects on people,” says professor Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice. “It produces paralyzation rather than liberation, and even if we manage to overcome the paralysis and make a choice, we are less satisfied with the result of the choice than we would be if we had fewer options to choose from.”

Without centuries of culture and tradition to guide us, without the personal knowledge to drive our selections, and in the face of the ever growing panoply of wine, we seemingly have no other place to turn than the advice of others — in the form of more than 35 iPhone apps, and literally hundreds of books on the subject with several more published every year.

But most of the time, that advice is bad, or at best, useless.

Someone Else’s Taste

Contrary to the impression conveyed by “authoritative” tasting notes and numerical scores from experts, not to mention what you might see MS candidates trying to do in movies like SOMM, science increasingly suggests that the experience you have when tasting a wine is uniquely your own.

In particular, one study conducted in 2015 found that the aromatic compounds released from a wine when it came into contact with saliva were statistically different across different individuals. That’s right, the molecules that make their way from the wine to our olfactory bulbs and to our taste buds are different for each of us than they are for anyone else. Thanks to the more than 700 different types of bacteria living in our saliva, we each literally taste something different and individual. This difference is so clearly distinctive and significant that some scientists have suggested it could be used forensically, just like fingerprints.

And that’s just the variation we can measure in a carefully controlled laboratory setting where saliva and wine mix in a petri dish.

Out here in the real world, we’ve not only got our individual saliva bacteria profiles, we’ve got all sorts of other variables that influence how we each perceive a wine. How well-rested we are; how well-hydrated; what we most recently ate and drank before that sip of wine; what kind of emotional state we are in; the kind of music that is playing in the background; the psychological influence of knowing the price or origin of the wine; and more.

Every single one of these factors can greatly influence our perception of a wine, as any honeymooning wine lover has learned, when they discover that the sublime wine they shared on a picnic blanket with their new spouse on a perfect day in Tuscany turns out to be not nearly as good as they thought when opened for visiting friends months later.

And all of this has to play against, and in many cases take a back seat to the personal preferences, prejudices, and experiences both specific and general that we bring to our sensory appreciation of any given wine.

So into all this complexity, we’re about to add the crazy variables that come with a particular wine’s interaction with a specific dish we’re eating while we drink that wine, and then, someone else’s opinion — no matter how well intentioned and informed — about whether we’re really going to enjoy the combination?

As they say in New York, “fuhgeddaboudit.”

One Plus One Does Not Equal Three

But what about those lightning strike moments, those organoleptic epiphanies that rock your world when you taste the perfect wine with the perfect dish and the heavens open and the choir sings?

They don’t really exist. Not really.

Do people have great experiences drinking a wine they love with something delicious they’re eating? Of course, that’s why we all eat and drink and pay for the good stuff when we can. But for more than 25 years I’ve been eating at some of the world’s top restaurants and getting wines paired by some of the world’s best sommeliers, and I can tell you that the times a particular combination of wine and food specifically selected by a chef and sommelier (or other non-professionals including myself) resulted in a sum greater than the parts can be counted on the fingers of one hand. With some fingers left over.

I’ve gone to specialized wine pairing events, where dozens of top chefs have cooked dishes specifically to go with the wines on offer. I’ve been treated to carefully composed menus by people whose business cards literally said they made their entire living as specialists in food and wine pairing. And more often than not, I come away disappointed or simply unmoved. Maybe the food is great, maybe the wine is too, but when I put them both in my mouth, sparks almost never fly.

In all honesty, about 10 years ago, I stopped getting the pairing flights of wine at restaurants to go with my multi-course meals. The reason? Invariably, there were several pairings that I simply didn’t care for — combinations that not only didn’t wow me, they actually didn’t taste very good. For the increasingly steep price of such pairings, I just kept getting disappointed, and found myself wishing I had spent my $150 on a nice bottle of Champagne instead, which is mostly what I do these days.

I’ve been told similar stories by countless winemakers, Michelin-starred chefs, fellow wine lovers, and ordinary consumers. Yet the rules of food and wine pairing persist. The apps proliferate. The books keep getting published. The wine pairing flights continue.

Because people still believe there’s a wrong choice to make, or believe that there’s an art or a science to making it.

Pernicious, Pretentious, and Preposterous

The so-called “rules” of food and wine pairing are bullshit. That goes for the old rules (i.e., red wine with meat, white wine with fish), which most people realized long ago were bunk. But it also goes for the supposedly new rules like matching the weight of the wine to the weight of the food, or avoiding acidity with sweetnes,s or pairing saltiness with more bitter wines.

For any well-intentioned guideline, there are countless exceptions that begin with the complexities of the dish’s ingredients and seasonings, continue through the winemaking decisions in the wine, and end with the personal preference of the diner. Each of which adds so much variability to the equation that any rule, any guideline, any “sure-fire-winner” of a pairing will fail for enough people enough of the time that any pretension at helpfulness is simply lame opinion, and nothing more.

The cultural baggage surrounding food and wine pairing and the vaunted expectations about it that persist in the marketplace are among the most pernicious and damaging features of modern wine culture. The tropes of perfect pairings and transcendent wine flights do for aspiring wine lovers what a steady diet of porn does for the sexual expectations of 13-year-old boys: warp them beyond the possibilities of satisfaction.

The idea that there is an art and science to wine pairing undermines individual tastes, thwarts personal initiative, suppresses curiosity, and ruins serendipity and impulse. The world of wine is so vast and colorful and interesting, it should chiefly inspire exploration.

Our expectations need to be reset. The bar needs to be lowered. We should absolutely be choosing wine to go with our meals, but our goals should center on enjoyment of both, and the idea of “mistakes” should be banished.

Are there combinations that I wouldn’t recommend? Sure. Heavily oaked Merlot and raw oysters would not be something I’d be inclined to recommend. But you know what? If you love Merlot so much that you want to serenade those bivalves with plummy goodness, then more power to you. No one should tell you you’re wrong, and no one should shame you for enjoying any wine under any circumstances. The most, nay the only, important things for any of us to achieve when pairing wine and food are our own enjoyment and the ongoing education of our palate.

Sommeliers are Still Super Useful

It’s quite important, however, that despite everything I’ve said above, you don’t leave with the impression that, with apologies to Shakespeare, “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the sommeliers.”

Yes, these immensely talented folks are the ones who put together the wine flights I have grown to hate, but clearly lots of people love them, and for good reason. Because while they often fail fundamentally to bring diners to dizzying heights of flavor, they do something quite important that remains central to the value of the sommelier profession: they introduce diners to wines they might not have ordinarily tried.

And that, folks, is why we still need sommeliers. These folks are the Starships Enterprise of the wine world — tirelessly seeking out new wines and new flavors, boldly buying things for one reason: our enjoyment.

While I rarely ask them to choose a specific wine to go with a specific dish, I love nothing more than having a conversation with a sommelier, telling them what wines I like, and asking them to recommend something they think I’ll enjoy. That’s what they’re really trained for, and the good ones are truly extraordinary at helping even the most experienced wine lovers expand their horizons.

Forget food and wine pairing – it only leads to disappointment. Stick with eating good food and drinking good wine. There’s no way you can go wrong if you’re picking both based on what you think you enjoy, and there’s no harm in getting advice on either, just so long as you don’t expect it to be magical.