There was once a time when everyone who was anyone in the world drank Madeira. Just ask America’s Founding Fathers, who purportedly toasted the signing of the Declaration of Independence with several bottles of a peculiar wine grown on a tiny island in way out in the Atlantic Ocean off the northwest corner of Africa.

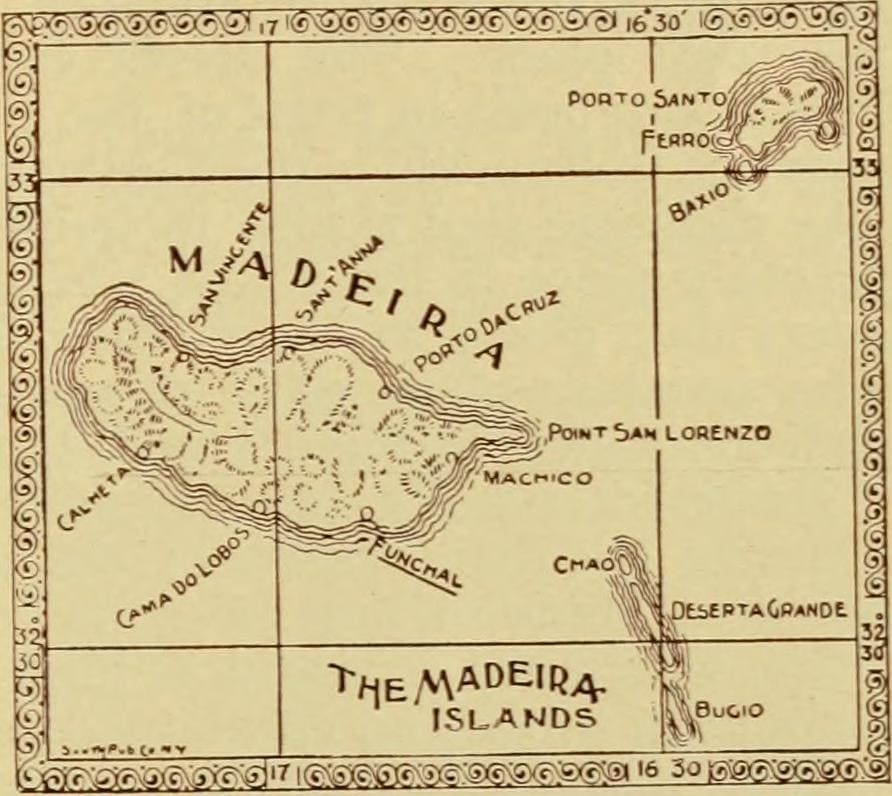

A combination of geographical and geological happenstance helped to make the island (really a tiny archipelago) of Madeira into a global wine powerhouse during the 17th century. Originally settled in the early 1400s after being discovered by Portuguese sailors, these tiny rain and windswept volcanic islands quickly became a port of last call for all ships leaving Europe for trade and exploration.

When you’re stuck on a small island, alcohol seems important. And when you have sailors visiting regularly, alcohol becomes essential. So after some initial forays into sugar cane production, the much more suitable industry of wine production ramped up pretty quickly, and by the early 1700s, Madiera was producing hefty amounts of wine that enterprising traders were not only consuming while in town, but bringing with them to sell elsewhere, but especially in America.

There was one problem, however.

During the Atlantic crossing, casks of wine exposed to saltwater and often punishing heat in the holds and on deck tended to turn to vinegar. But then someone decided to harness the power of fortification.

How to make an immortal wine

Taking a page from the Port wine industry, some enterprising soul on Madeira realized that adding a bit of pure alcohol to the wine (a process known as fortification) kept the wine from turning into vinegar.

With one simple innovation, the wine industry of Madeira was saved from being a footnote in history. But it would take one more insight to turn Madeira into one of the most important wines in history.

You see, while the addition of alcohol to the wine prevented it from turning to vinegar, that fortification didn’t protect the wines from the predations of seawater and heat that accompanied the long voyage by ship to America or around the Horn of Africa to India.

But for some time, the winemakers on Madeira neither knew nor cared about that journey. After all, they got paid to load their barrels of wine onto ships and then waved at them as they headed West while counting their money. It apparently took a (rare) batch of unsold wine being brought back to Madeira for the winemakers on the island to truly understand what they had done.

The wines that arrived in America or the Indies were not the same wines that left the little island of Madeira. The conditions of the voyage transformed the wines into something else entirely. A bit of oxidation here, a bit of heat there, a splash or two of seawater or rainwater, and what arrived at Cape Cod was not just a fortified white wine but a nutty, sometimes salty, caramelized elixir unlike anything else on the planet.

And you know what? People loved it.

They loved it for the flavors, and for the fact that the wine, once subjected to the kind of abuse that a long sea voyage could provide, basically became bulletproof. Bottles of Madeira can literally last for centuries. The idea being that all the bad things that can happen to wine have mostly already happened to these wines.

Once the folks back in Madeira realized that everyone loved their wines, not as they had made them, but as they had evolved over the course of the voyage, the industry began to develop ways of recreating and controlling the effects of the sea voyage, practices which the industry still uses today.

Starting in the late 1700s, Madeira producers began subjecting their wines to heat and air, as well as aging them in casks for long periods of time, eventually developing the various styles of Madeira wines that exist today. There are several variations on the modern process of producing Madeira, from scientifically calibrated artificial heat (for cheaper wines) to leaving barrels outside in the sun for a long time (for more expensive wines), but no matter the technique, the process is known as estufagem.

Five Types of Timelessness

There are a number of fringe exceptions in the odd, boutique world of Madeira production, but largely the wine consumers encounter in the market will be one of five types, each corresponding to the four primary white grapes, and one red, that are used to produce most of it.

Plain old Madeira

Wines simply labeled Madeira, some explicitly designated for cooking, will be the cheapest version of the wine, and are usually made with the red grape Tinta Negra Mole, which makes up 85% of the island’s production. These wines are quite sweet, and will be largely uninteresting to wine lovers with any level of discernment.

Sercial

Made from the white Sercial grape, which for unknown reasons is called Esgana Cão or “dog strangler” on the Portuguese mainland, these wines have searing acidity and have very little perceptible sweetness since they are allowed to ferment nearly to dryness before being fortified. They are nutty, often salty, and can be surprisingly refreshing. Technically these wines can have between 9 and 27 grams per liter of residual sugar.

Verdelho

Made from the white grape Verdelho (not to be confused with Verdejo, which is another grape entirely) these wines are usually lightly to moderately sweet, their fermentation being halted somewhat early by fortification. Flavors of coffee and caramel are typical. Sugar levels are usually between 27 and 45 grams per liter.

Bual/Boal

Bual is another white grape that ripens rich and golden in Madeira, whose fermentation is halted to create a sweet dark concoction of raisin, date, and other dried fruit flavors, with sugars between 45 and 63 grams per liter.

Malvasia / Malmsey

The sweetest category of Madeira, but also one with unusually high levels of acidity, wines made from the Malvasia grape aim to have between 65 and 120 grams per liter of sugar. These wines taste like coffee nibs, butterscotch, toffee, candied nuts, and sweet cream, but possess enough acid balance that they never get cloying.

Buying and Enjoying Madeira

Good quality Madeira will always be clearly labeled (ancient bottles notwithstanding), and will usually have one of the above four white grape names prominently displayed on the bottle. You may encounter a few other grape varieties of Madeira, including the moderately sweet Terrantez (definitely not the same grape as Torrontes), a historically important variety that is seeing something of a resurgence after nearly disappearing for a century or so.

A few other styles of Madeira exist that have proper names that aren’t grape varieties, the most common of which is “Rainwater,” usually made with the Tinta Negra Mole grape. While usually considered to be less refined than the “noble” white grape varieties, this style can be quite tasty when made by a good producer.

Just as with Port, the grapes for Madeira are grown by thousands of independent growers, but almost all Madeira is made and bottled by one of a dozen or so companies. However, if you think that means you only have a few names to look for in the store, think again. Some of those companies, like the Madeira Wine Company, have dozens or even scores of different brands under which they sell their product. Complicating matters, these few producers also sell wine in bulk to outside companies (including top Port producers) who then bottle the wine under their own brands.

And that’s just the modern industry.

When it comes to dusty bottles with 50 to 250 years of age on them, all bets are off in terms of what name you’ll find printed or stamped on the bottle. The pre-modern Madeira industry was a wild west of producers, bottlers, shippers, traders, blenders, pirates, and more.

Older bottles can feature the initials of the grower, the name of the blender’s firstborn daughter, the name of the ship that brought the bottle to America, the name of some other wine company that commissioned or bought the wine, and so on. Those interested in buying truly old Madeira have a complex world of provenance and history to negotiate.

The rest of us, however, will likely be buying from one of the modern producers and blenders. Names such as Barbeito, Cossart, d’Oliveiras, Justino Henriques, Madeira Wine Co (aka Companhia Vinicola da Madeira), Madeira Wine Institute, Henriques & Henriques (aka H&H), Opici, H.M. Borges, Broadbent Selections, Artur de Barros e Sousa, or the Rare Wine Company will be the most common, and usually come stamped or screen printed on the front of the bottle (paper labels being less common by tradition).

One of the great things about drinking Madeira is knowing that you’re tasting something that isn’t far off of what folks like Thomas Jefferson might have been drinking more than 250 years ago.

Most Madeira over $25 will either be a multi-vintage wine with an average age stamped on it, similar to Port, or it will be from a specific year, which will be clearly indicated, sometimes in conjunction with the word colheita. Strange fact, but the Port industry has legal protection for the use of the word “vintage” on labels, so you won’t ever see that word on a bottle of Madeira.

All fine Madeira bearing the name of a grape variety must be aged for at least 5 years before bottling. Occasionally you’ll also see designations like Reserve or Extra Reserve, but the years of aging that these classifications represent will almost always be stated on the bottle, so remembering that Special Reserve means 10 years of aging won’t be required.

One of the great things about Madeira (which honestly had a lot to do with the adoration shown for the wine by the American colonies and pretty much everyone in the pre-refrigeration age) is that you don’t need to worry about drinking the whole bottle, and you don’t need to worry about where or how you store it, other than putting the cork back in so fruit flies don’t find their way in. Leave a half-consumed bottle on a shelf in your sunny kitchen for 5 years between glasses and you’ll find it just as tasty as when you last tried it.

That isn’t to say Madeiras don’t evolve. They certainly do, albeit very slowly. But most importantly, they just don’t spoil.

I don’t buy a lot of dessert wines because I find I can rarely finish a bottle unless we have a lot of guests over for dinner. Drinking a glass of sweet wine isn’t something I want to do night after night. But I have no compunction about paying decent money for a bottle of Madeira on the other hand, because I know I can make that purchase last. For decades if necessary.

That said, the salty, nutty, caramelized, café au lait, raisined, and dried fruit flavors of Madeira are not for everyone. I tend to prefer the drier, saline, and savory flavors of Sercial more so than the richer, sweeter wines. But all manner of Madeiras are now being used as ingredients by leading mixologists around the world, so there’s been a rise in interest generally for these wines.

One of the great things about drinking Madeira is knowing that you’re tasting something that isn’t far off of what folks like Thomas Jefferson might have been drinking more than 250 years ago. No other wine in the world can provide as accurate a window into the true flavors of the past.

As the 1800s progressed, the transatlantic crossing became easy enough that people didn’t need to stop for resupplies, and Madeira pretty much fell off the map, earning it the unfortunate nickname of the Forgotten Wine Island. While the lapse into near obscurity was doubtless painful for the Madeirans, they are lucky that they happen to make the one kind of wine in the world that will never be too old to drink.

I recently had the opportunity to taste through a bunch of Madeiras from several producers, so here are my notes.

Tasting Notes

I did not note the alcohol levels of these wines as I tasted them, but most Madeiras are fortified to just shy of 20% alcohol.

1969 d’Oliveiras Sercial, Madeira, Portugal

Light coffee-colored in the glass, this wine has a slightly salty, pine sap quality that gives way to roasted nuts, vanilla, and a long finish of honey-roasted nuts. Mouthwatering acidity and incredible persistence in the mouth. Very delicious. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $325. click to buy.

1997 d’Oliveiras Tinta Negra, Madeira, Portugal

Light amber in the glass, this wine smells of coffee, nuts, and nail polish remover. In the mouth, dried and roasted orange peel, mulling spices, and roasted nuts accompany a medium sweetness. Decent acidity. Made from the Tinta Negra Mole grape which is the most common on the island, making up 85% of the acreage. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $150. click to buy.

1988 d’Oliveiras Terrantez, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in the glass, this wine smells of nail polish remover and roasted nuts. In the mouth, lightly sweet flavors of vanilla, roasted nuts, and dried herbs have a bit of heat to them. There’s a sense of imbalance here, but some pleasure. Once almost extinct due to its relative fragility, Terrentez is the new darling grape of Madeira, with growers being offered bounties for planting it these days. Score: around 8.5. Cost: $200. click to buy.

MV d’Oliveiras “5-Year” Red Blend, Madeira, Portugal

Light to medium amber in the glass, this wine smells of maple syrup and roasted nuts. In the mouth, vanilla, roasted nuts, and nougat flavors are lightly sweet. Decent acidity. Score: around 8. Cost: $35. click to buy.

1968 d’Oliveiras Boal, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in color, this wine smells of coffee and bitter orange. In the mouth, camphor wood, bitter orange peel, brown sugar, and sawdust flavors surround a core of medium sweet dates and candied citrus. There’s a woody quality to the finish. Score: around 8.5. Cost: $390. click to buy.

1990 d’Oliveiras Malvasia, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in the glass, this wine smells of coffee-flavored candy and orange peel. In the mouth, vanilla, coffee nibs, orange peel and a mix of mulling spices sit silky-textured on the tongue and linger for a long time. Moderate to very sweet, but with excellent acidity. Quite tasty. Score: around 9. Cost: $190. click to buy.

NV Barbeito “Tres Pipas” Bastardo, Madeira, Portugal

Light amber in color, this wine smells of roasted nuts and orange peel. In the mouth, the wine is seemingly almost dry, with little perceptible sweetness and a tight tannic texture. Flavors of brown sugar, vanilla, roasted nuts, and dried flowers linger through a very long finish. Excellent acidity. The Bastardo grape, known elsewhere as Trousseau, is fairly rare in Madeira. Pipas were the historical name of the bulk shipping casks for Madeira. This wine is a blend of 2011, 2012, and 2013 harvests. Score: around 9. Cost: $60. click to buy.

1994 Barbeito “Frasqueira” Verdelho, Madeira, Portugal

Light to medium amber in the glass, this wine smells of crushed nuts, nail polish, and orange peel. In the mouth, the wine has great acidity, which makes the orange peel, nuts, and vanilla flavors have an almost earthy component. The wine is tangy and pretty tasty. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $225. click to buy.

MV Rare Wine Co. “Historic Series – Charleston Special Reserve” Sercial, Madeira, Portugal

Light amber in the glass with glints of green, this wine smells of crushed nuts and citrus peel. In the mouth, faint tannins cushion salty flavors of nuts, citrus peel, candied fruits and a long vanilla scented finish. Lightly sweet, but with great acidity. Score: around 9. Cost: $50. click to buy.

MV Rare Wine Co. “Historic Series – Baltimore Rainwater Special Reserve” White Blend, Madeira, Portugal

Palest amber in color, this wine smells of raisins and lemon peel. In the mouth, the wine is almost delicate, with lemon peel and roasted nuts, beeswax, and a fantastic saline quality that makes the mouth water. A stunningly great wine with an epic finish. Modeled on an early 1800s batch of Rainwater Madeira and based on mostly Verdelho but also with the addition of wine from a 1950s tank of Negra Mole that wasn’t aged in oak. A triumph of blending and a fantastic window into what a generally maligned style of Madeira once was at its best. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $50. click to buy.

MV Rare Wine Co. “Historic Series – Savannah Special Reserve” Verdelho, Madeira, Portugal

Light to medium amber with coffee-colored highlights, this wine smells of dates, nuts, and brown sugar. In the mouth, the wine is lightly sweet, with a lovely salty edge and flavors of honey roasted nuts, vanilla, and candied fruits, with a touch of alcoholic heat in the finish. Compelling and dynamic. Score: around 9. Cost: $50. click to buy.

MV Rare Wine Co. “Historic Series – New York Malmsey Special Reserve” Malvasia, Madeira, Portugal

Light coffee-colored in the glass, this wine smells of coffee nibs and brown sugar. In the mouth, bitter orange, angostura bitters, and licorice root mix with dark fruitcake flavors. Moderately sweet, decent acidity. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $50. click to buy.

2001 Henriques & Henriques Sercial, Madeira, Portugal

Light amber in color, this wine smells of toffee and tangy citrus peel. In the mouth, orange peel and vanilla flavors are tangy and salty, and bright thanks to fantastic acidity. Lightly sweet and delicious. There’s a lovely delicacy and vibrancy to this wine that is very compelling. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $125. click to buy.

2007 Henriques & Henriques “Quinta Grande” Verdelho, Madeira, Portugal

Light to medium amber in color, this wine smells of burnt orange peel. In the mouth flavors of coffee nibs, brown sugar, orange peel, and licorice root have a light sweetness and a faint tannic texture. Decent acidity. Quite pretty. This is an unusual wine in that it comes from a single vineyard parcel – quite a rarity in the world of Madeira. Score: around 9. Cost: $60. click to buy.

MV Henriques & Henriques “20 year Medium Dry” Terrantez, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in color, this wine smells of tangy dried citrus peel and honey roasted nuts. In the mouth, candied almonds, bitter orange, and nut skin flavors have a distinct tannic grip with barely perceptible sweetness. Quite tasty. Score: around 9. Cost: $145. click to buy.

2000 Henriques & Henriques Boal, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in color, this wine smells of almonds and spices. In the mouth, brown sugar, orange peel, and roasted nuts have a strong alcoholic heat to them, which makes this a bit spicy and heady. Score: between 8 and 8.5. Cost: $90. click to buy.

MV Henriques & Henriques “20 Year” Malvasia, Madeira, Portugal

Coffee colored in the glass, this wine smells of coffee and licorice. In the mouth, black tea, coffee candy, licorice root, and treacle flavors are thick and silky on the tongue. There’s also a fairly serious tannic grip to this wine. A bit… intense. Score: around 8.5. Cost: $140. click to buy.

1981 Henriques & Henriques Verdelho, Madeira, Portugal

Medium amber in the glass, this wine smells of nuts and caramel. In the mouth, the wine is simply amazing, thick and silky on the tongue with moderately sweet and salty nut skin, nougat, caramel, and toffee flavors that soar on waves of vanilla-scented air for minutes. Amazing acidity. Totally outstanding. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $325. click to buy.