Few people in history achieve true mononymity, fewer still in the world of wine. But for 50 years, one American importer of some of the world’s greatest wines was known and revered as simply, “Martine.”

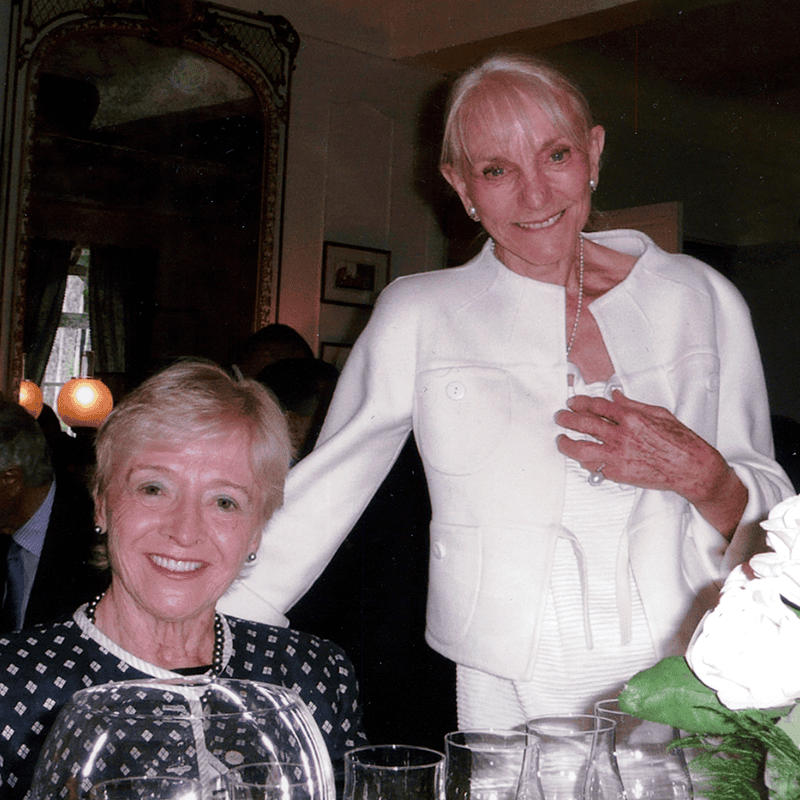

On February 9, Martine Saunier, famed wine importer and founder of Martine’s Wines died at the age of 91.

A pioneer in many senses of the word, Martine was known for being the first American female wine importer in modern times, one of the first importers of fine Burgundy into the US, and then eventually as the importer responsible for some of the wine world’s greatest names, from Burgundy legend Henri Jayer to the revered wines of Château Rayas in Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

Martine was twice decorated by the French government with the title of Officier du Mérite Agricole, and once with Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. She was a Chevalier du Tastevin, a member of Les Dames d’Escoffier, and served on the national board of the American Institute of Wine & Food.

I had the distinct pleasure of spending a significant amount of time with Martine a few years ago as we explored the possibility of me co-authoring her memoirs. I interviewed her extensively and was treated to many stories, both of her early life in Europe, as well as those from her rise to become an iconic importer and respected figure in the world of wine.

“My life has never been dull,” said Martine. “I have been privileged to live an adventure that still yields new discoveries every day.”

In tribute to her, I’d like to offer some of her stories, lightly edited for clarity, but otherwise entirely in her own words. For those who never had the pleasure of sitting at a table as she regaled her guests with a sparkle in her eye, a winning smile, and a bottle in hand, here is Martine at her finest.

Early Years in Paris and the War

Saunier was born in Paris and grew up as the eldest of four children in the 1930s, between the two World Wars.

When I was a baby, before the war, my parents would take me to Champs Mars and I would sit on the pile of sand and look at the kids and I would say, “I’m not interested.” I was raised by adults and listened to what they said all the time, and I thought they were more interesting than the kids.

My parents put me in the Girl Scouts when I was 12. A year later I was the leader.

I was the oldest of 4 kids.

My parents’ future was ruined by the [First World] war. My father wanted to be an architect. He was called up when he was eighteen. One day he was running behind a soldier, and the soldier got the shell, but my father got shrapnel into his hands. They were completely torn apart.

After the war, all the people he knew were dead. He couldn’t be an architect. My mother was 6 years younger and her father took all the money and left her family. She decided she could be a seamstress, bought some needles, and went and got hired. Six years later she had 26 apprentices in a big firm.

In the 30s she met my father and he told her once they were married she couldn’t work anymore. She never had a bank account until she was 70, in the 1980s. The women’s right to vote was much later. The abortion vote was much later. So growing up I thought, “God, this — I don’t want to have six kids.”

My father loved soccer. He played before the war. He also loved tennis. On weekends he and I would go to soccer games and horse racing and tennis. I was always behind him, he was happy,

We all sat for dinner as a family. Once a week we had to go through the motion of showing our report card. If I was second in my class he would say, “You should be first.” He was never satisfied.

I remember when the little Jewish girl in my class disappeared. As a kid, you don’t know why. No one talked about that during the war. The woman was French as well as Jewish.

I remember playing with kids, a boy and a girl my age in the west of Paris. The little boy opened a drawer in a desk and there was a gun. We all looked at it. “My mother keeps this in case there’s a German and then she will shoot him,” he said. The Germans were the enemies. We were told to behave, and never answer the door for a German.

I went to school by train. We could hear boots at night in the street because of curfew. We were careful to have the radio under a blanket to listen to the BBC at night.

I remember friends of my father, they had a house that was unoccupied, with a yard full of big weeds where we’d run around. A friend of my father’s came by and said he had to leave a package in the garden for a while and told us not to touch it.

Apparently, my father said he didn’t want to get involved. He had 2 kids and his wife was pregnant. My father was anti-German, though.

After the war, he couldn’t hold a hammer or put a nail in the wall or change the wires. I was taught to do all that.

When the Second World War started, my father moved us to Burgundy. He was 41 years old and already a veteran. I remember my uncle one morning took me to what felt like the corner of the world, there was a tank there with a blond German in it and he had a big piece of Gruyere. My uncle looked down at me and said, “When I think of this and what we went through and now we’re starting all over again” and shook his head. Four days later he died.

As a child you assimilate, and you try to understand the seriousness of things.

I came back to Paris after 2 years, and I remember the bombing. We had the sirens, the DC8 Superfortresses as they dropped the bombs on the German ammunition factories on the Seine and tried to evade the Messerschmidt.

We were in a house, underneath the house was a cellar, but we knew that wouldn’t protect us. “We might as well see what is happening as it happens,” said my father. We were on the first floor, and opened the shutters. You could see the light of the anti-aircraft from the forest where the guns were. And every time the bombs hit, the bed would jump. It was really the reality of war. In the morning we’d go out into the streets and look for scraps of shells in the rubble.

When I was living with my aunt in Burgundy we had chickens and rabbits, cows and fruit trees, and we made our own butter. Back in Paris we had food tickets that bought one slice of bread, a little sugar. I remember waiting in long lines with all the younger children of the neighborhood. We were all starving. I became like a stick, and a Polish doctor gave my father extra meal tickets for me, telling him that I needed to eat.

Summers in Macôn

In 1944, Martine began spending summers in Macôn, traveling across the Demarcation line into the Zone Libre on a train with the Red Cross, subject to terrifying inspections by the Germans patrolling the border. But once on her aunt’s farm, she settled into the rhythms of Burgundy in the summer.

Prior to the harvest, there was great excitement. We didn’t hire people to come pick the grapes. In that neighborhood of Macôn we all had small vineyards: 3, 4, or 5 hectares. So what we did is that between neighbors, they decided which vineyard should be done first. Based on the exposure and when things would ripen. We had a very nice vineyard with great exposure and so very often, we were the first to start, and people came to us to help with picking grapes. Then when they picked their grapes we would go and give the time, the same number of days to our neighbors.

I was 11 years old, but I was told, “You have to pick grapes.”

Of course, I remember the early mornings, with frost, it was cold and wet sometimes. We’d go to the vineyards at 7 AM. I had my little serpette knife, it was not a secateur, but a sharp little thing, and I was told how to do it. I had my pail, and had to give it back full, and I was not supposed to drag behind.

I took the job very seriously. By 10 o’clock in the morning, the winemaker’s wife Jean would bring this big basket full of fresh bread and saucisson and ham and paté de foie and bottles of wines, and we’d stop and have a snack, if you’d call it a snack. And of course, the bottle went from one row to another, and everyone drank from the same bottle.

I took my little sip. There was no water available, but we drank a mouthful of wine, a light wine from the previous year.

Later in the day, the luncheon was prepared by my aunt, and it was always delicious food. You had poultry and rabbit in red wine sauce and roast pork, and it was a full meal: appetizer, main course, and dessert before going back to the vineyard.

All that took about an hour and a half, and everyone was feeling a little punchy, but we went back to the vineyard and we’d work until 5.

The grapes were carried away in a bain, which is this wooden thing with two handles that the winemaker put on the back of a big cart that would dump into a wooden vat.

Ten days before the harvest, the winemaker would hose down each vat, scrub it with a brush, and rinse it again, and he did the same thing with the press. We had a very old wooden press that was built like a puzzle. The press was made of solid oak, with some pieces weighing about 100 pounds. He couldn’t do it himself, he had his helpers, and it was ready for the harvest.

We had three vats for red and also for white and ten days before the harvest the winemaker would hose down each vat, scrub it with a brush, and rinse it again, and he did the same thing with the press. Very clean. It was amazing, just plain water and a lot of barrel cleaning. I followed everything. I was fascinated. The winemaker had two sons my age, and unless I went to the village, I stayed home mostly, following the winemaker. I was fascinated with his work. I found out how to clean a barrel with water and sulfur, lighting the wick and putting it inside to sterilize the barrel. The barrels were repaired carefully.

We also had, of course, white grapes pressed immediately, and juice transferred to the barrel, but the red grapes, we had fermentation for four or 5 days, with no addition of anything. Certainly, we did not use yeast. One guy was inside the tank, holding to the edge and stepping crushing grapes with his feet. We were supposed not to get close because they didn’t want us to fall into the grapes, as it was very dangerous for asphyxiation.

But when we started to press the grapes, we had these little side walls next to the press, and we could step inside these little walls, and crush the grapes with our feet, and it was great fun and we loved it. In fact, we felt that we did a good job, and it was expected from us.

So anyway, the time of the crushing, starting in the morning, then the press, and after transferring wine to barrel, it was really a long job sometimes. We had to take the first crush then we dismantled all these pieces of wood and shovel with a pitchfork the grapes and press again a second time. I was pushing the bar to crush, crush, crush, and sometimes until 1 AM. Of course, it depends on when you started, but I was completely left alone, and nobody said you have to go to bed or nothing.

In 1947 however, it was a splendid vintage. Gorgeous weather, very warm, we had high temperatures in August like 40 degrees centigrade, I remember it was a really hot summer. Anyway, in 1947 when we pressed the red grapes it was amazing. We had a huge vat under the press, and all the neighbors came and tasted the wine and said it was fantastic. I tasted, too. I borrowed a silver cup from my great uncle, and tasted, and I thought, “Really, whew, this is amazing.” The fruit and the delicatesse of the wine, I was so enthused.

So I exceeded, perhaps, my normal consumption. You know, you don’t have much in the cup but one mouthful after another with the next guests coming to check out our wine, all of a sudden I felt dizzy.

But I didn’t mention it to anybody. I left the press, went upstairs climbed four-legged up the stairs, into the kitchen, went into the cupboard, cut some bread and took some salami and made myself a big sandwich. No one was home. I was hoping nobody would see me. I got sober really fast. I said, “Well, that’s it, too much wine is not good for me.” Nobody knew about my adventure, I didn’t mention it, but it was a life-changing experience for me. It’s amazing how children can take a conclusion about their experience.

I loved my summers in Burgundy because I was free as a bird, I loved to pick the grapes. We were all young people, and we listened to the old wise guys and there were lots of laughs, and sometimes, you know you had people who were hard to understand, they had a patois they spoke amongst themselves. It was really great fun and we worked very hard, even though we never got a nickel, you know. It was free work. And we didn’t expect anything anyway. So that was my experience with wine at an early age.

As I got older, from 13 on, at home, especially in the summer when my parents came and spent the whole month of August with our cousins, I was told to get the wine ready for lunch and dinner.

There was one barrel of white and one barrel of red in the cellar which were supposed to be for our daily consumption. There was a little rubber tube that hung on the wall. I would take that rubber tube and put it in the red wine barrel, and of course, as the quantity of the red wine in the barrel went down, there were what you call “flowers” on the wine. Because you know we didn’t top the barrel of course. So I was told that you go down and then you suck the little tube and you put it in the bottle and when it is full you stop it and you go to the next bottle. After I would take the tube out, rinse it in water and put it on the wall. That was my daily job. And I didn’t think of it, you know, but actually, you can’t help but to taste a little wine every time you do that.

Over the years, we had some bottles we saved, because it was a good vintage. I tried wine all the time, and also on the great outings we had as a family to go to La Maison du Beaujolais, in Macôn, where we tried the new Beaujolais from all the different cru. You could get a split of all the Beaujolais, and the family went and we put all the little bottles out and we tried each cru, and we could see the difference between them.

Sometimes we also went to Pouilly-Fuissé to try some wine as a family, and I developed a palate. I was not supposed to drink. And I didn’t drink actually, I spit it out. I knew I wasn’t allowed to drink, but it wasn’t a question of being allowed, it was my common sense. I had experienced already being dizzy once, and that was enough, so I think that was how I developed my palate.

My father was very fond of Côte Rotie and Hermitage and so we had a few in our cellars. And then we’d also have Champagne in Paris. Ayala was my father’s favorite. For big occasions, the holidays and birthdays, we’d have Champagne. And all together drinking wine was part of a meal. Of course not during the week, when we went to school. It was a weekend thing. I was never and none of my siblings were ever drunk. We just tasted wine at the table.

A Career Takes Flight

Determined to make her own way, Martine left home on the day of her 21st birthday with a single suitcase, 10,000 Francs, and her dreams.

On my 21st birthday, I left and went to England. I went to work for a family of British teachers who had spent their whole lives in India as private teachers of the Maharajas. They rented rooms to people to survive. I met them a few months earlier and I said, “Do you know anyone who needs help doing babysitting?” They said, “Come help us we’ll give you 3 pounds per month for pocket money.”

I knew they were intelligent and well-read. And quite old. Mrs. Turner, I think she was the first female graduate of the University of Colorado. She was in her 70s. In the morning I made beds, did washing of dishes, polished silver, cleaned the bathrooms. I knew how to do it anyway. One of the guys that was living on the premises, he was a scientist working at a big factory making drugs for animals. He said, “You should go to the factory, they have some French people there, maybe you could ask for a job.”

So I went, but I was told, “You shouldn’t be here, you don’t have a visa, you are technically an illegal worker.” But they gave me a pamphlet to translate into French. After lunch I would run down two miles, and type and come back, and I provided the translation.

They liked it. “You are doing very well,” they said, “and now we need you to translate a magazine for the French Africa companies. If you can do it, we will ask for a work permit for you, but until it comes through you won’t be able to go to France.”

Two months later, I had a full-time job. I told Mrs. Turner, “Now I will be officially employed, but I would like to stay here, I can help with the dishes and cleaning on the weekends in exchange for my room.” I stayed two years.

All of a sudden, I was in charge of this magazine about animal medicine. It was very complicated. They had descriptions of cattle deep in Africa. Fortunately, they had a technical library where I could read about all these diseases.

I went back to France in 1958. But I couldn’t get a job and had to live at home. There was no place to rent. France was in bad shape in those days. So somebody said, “Maybe you should apply to British Airways,” as they were looking to hire at Le Bourget Airport. I was hired for a summer job. It took me 2 hours to get to the airport. I had 10 hours of work at the airport. Very often I didn’t have a weekend. But I overcame my shyness speaking on the loudspeaker and taking care of VIPs. It was a very interesting time.

I supported myself with British Airways for a year, but I lost my friends because I was never around and I worked like a dog. After that, I went to Spain for a month and perfected my Spanish and started looking around for any job I could get.

I was hired by the Tunisian embassy as a part-time secretary for the Consul General for two afternoons each week. After my first afternoon they asked if I could work full time. But eventually KLM Airlines called and offered me a job. I was still living with my parents.

One day on the train back home, I saw the newspaper with an ad for a Japan Airlines – Air France Partnership that was going to open a transpolar flight from Tokyo. They needed someone who had experience with airlines and who spoke English. I waited a week and applied, and the following Saturday I felt like I was in front of a jury, a whole panel of French, Japanese, and British managers.

They offered me the position of assistant to the General Manager of Japan Airlines. He was an ex-Air France guy, who was based in Rio. He had 6 kids and had to come back to France.

I had to start everything from scratch, and then not long after, the GM had to travel to Spain to cover Europe for JAL and in his absence I had to run everything. The Japanese guy in the office was told, “If you have a problem you talk to her.” I was running everything. It was amazing. You have no idea the adventure I had.

One day I had to prepare for the visit of the sister of the Emperor of Japan. She was coming to Paris. I had to check with the nightclub, the Lido, to establish the itinerary of the Princess, and I met some guys who had nightclubs in Tokyo. They were in Paris to book new talent. I went with them to different nightclubs. They said, “Please come to Japan we want to take you to the nightclubs.” On my next business trip to Tokyo, they picked me up at the hotel. I went into this dark little nightclub, where they walked me to this little table at the front of the stage, and on comes Louis Armstrong.

At the end of the show, the lights came up and the black woman sitting next to me, who turns out was his girlfriend, said, “Hi honey, let’s go see Louis.” So we went backstage. He was the nicest gentleman, so kind, so fun.

I said, “I am Martine, I’m visiting the owner of this nightclub, and he invited me to come to the concert.” Louis was completely at ease, he had no problem at all. We all went out to have a drink after the concert. We talked about music. I knew his music. They were such a nice couple. He gave me a big 78 disk dedicated to me.

Japan Airlines finally decided I would go on the inaugural transpolar flight. I left from Japan for it. It was incredible really. This was 1962 or 1961. Not long after I came back to Paris my Japanese manager was recalled to Japan for a higher position. He was replaced by a little swarthy Japanese guy who didn’t speak French. He decided no woman was going to be in charge, not in his territory. I said, “OK, I’m not staying here.” I resigned, and knew that because of all of my connections, I could easily get another job.

Within 24 hours I was called by SwissAir and I was hired to do PR for the airline in 2 minutes flat, for a much bigger salary. I found a very bad apartment, with money lent from my father, with a big bedroom on the 15th floor, and prepared to start my new job.

A few weeks later I walked in for my first day, and was greeted at the door with, “Madam Saunier, we are glad you are here. We had a crash last night. You are in charge. What do we do?”

It was a nightmare. I’ll never forget that. You can work in PR for airlines and go your entire career without a crash. To have a crash on your first day is like the reverse of winning a $50 million lottery. What are the chances? It was like a brick landed on my head. I was speechless, paralyzed for a moment. People were running and phones were ringing, it was turmoil. That was the most horrible experience, but I fortunately handled it well. I never doubted I could handle it.

That was a big step for me. Those days in France it was impossible to get a phone in your home. But SwissAir made a call to the French Minister of Communication and I had a phone in my apartment within a week, with apologies for the delay. “You’re 24 hours on duty now,” I was told. That was my SwissAir experience.

One day, the French General Manager asked me to write an article about American Airlines, which didn’t seem like a good idea to me at the time. I wrote to my boss the President in Zurich, and explained why I didn’t think it was a good idea. The President came to town and took me into the office of the GM, and said to him, “You asked her to do an article and she refused. She was right. From now on, please listen to her.”

I didn’t know I was so competent. As I grew and I took more responsibility, I knew how to handle it. At the time, no woman had the kind of position I had with SwissAir. I took the head of Le Figaro to lunch. I had to pay and order the wine, and no one said a thing about it. I was impressed. The French got the program that I was in charge and no one questioned my authority.

This was the background I had from the beginning. I didn’t ask for anything, it just happened. But how can a woman make the decision to start her own business? I had this feeling that it was just the way it should be. I didn’t have any problem making a decision.

From Housewife to Importer

After falling in love with an American doctor 15 years her senior, Saunier left her career behind and moved with him to the Bay Area in 1964 and eventually married in 1967. She helped to raise her husband’s children from a previous marriage, one of whom would go on to become Huey Lewis of Huey Lewis and The News. She would divorce in 1977 after 10 years, but not before making the fateful decision that would shape the rest of her life.

My determination, once I was in America, was to taste some good California wine, but there wasn’t much there. The wines weren’t great and I couldn’t even make vinegar from the leftovers because many were pasteurized! I tried a bit of Cabernet from Napa and Sonoma, but the only one I really liked was Beaulieu. What I really wanted was a good Pinot Noir.

But because I liked their wines, one day I drove to Beaulieu in Napa. No one was around. Eventually, I knocked on the cellar door, and when it opened I explained who I was and that I was French. The man who answered the door began speaking in French and explained that he, André Tchelistcheff, was from Russia but had trained in Bordeaux. He was so happy to be speaking French. I told him that I liked his wine very much, and wanted to know where I could find some good Pinot Noir in California. He said, “Look at this soil. This is not the soil for Pinot Noir. If you want good Pinot Noir, Madame, you will have to go to Burgundy.”

I said, “Thank you very much,” and I turned around and went home.

When I was married, a lot of the doctors in our social circles had started to collect Bordeaux and California wine. They would put bottles on the table when we got together—Inglenook, Beaulieu, Charles Krug, and so on. One day, as I was passing the table, one doctor said, “Try this wine—you tell us what it is.” I took a sip and said, “Oh, this is Louis Martini Cabernet Sauvignon.” They were all astonished. “What,” they said, “How could you know that from one taste?” I told them that I had tasted it 2 months ago at the dinner that one of them had thrown. I impressed them with that.

“What about French wine,” they asked. Did I think I could get them some good French wine?

Since I really did want some good Burgundy, I set about trying to figure out how to get some in California. My doctor friends said, “You buy some, we’ll pay you back.”

I found Draper and Esquin and tried some wine they imported from Avery Bristol. I bought a little bit of this and a little bit of that, but none of it was very good. One day I went to open a Santenay, and all the corks had leaked, the wine was completely oxidized and heat-damaged.

I went back to the merchant. “Technically my wine is good,” he said.

“No, it is leaky, no it’s not good,” I said. He didn’t want to reimburse me, but I fought and got my money back. But this was too much. It should not be so hard to get a good bottle of Burgundy.

Someone told me they had a friend who was a German importer named Hillebrand in SF bringing in beer and German wines as well as some from France. I called him up and asked about Burgundy. He said, “I have some great Burgundy.”

“I doubt it,” I said.

“I’m going to send you one mixed case,” he said. “You taste it and let me know.”

I tasted the wine and it was horrible. I went back and told him how horrible it tasted, and he said, “How dare you!”

I said, “I can’t believe no one imports good wine from from small producers.” After he calmed down he said, “OK, you do that and I’ll give you 5% commission.”

So in May of 1969, I took a charter flight from Oakland to Amsterdam, bought a cute little Volkswagen in Antwerp, and started my tour.

Have Volkswagen, Will Travel

Driving around France in the early 1970s in her Volkswagen beetle, Saunier discovered the ideal synergy of skills acquired in the corporate PR world and her instincts for wine quality that led her way to many small producers whose names were not yet well known, but who would eventually be spoken of with reverence.

I had no other connection to wine other than my childhood surroundings in Macôn but that didn’t scare me. My mother and a friend of mine were waiting for me when I arrived and we drove immediately to Champagne, and I thought maybe we could go to Philipponat. There was no one waiting to visit that place. You could walk in and taste Champagne and the GM would sit down and talk to you like you were important. I was surprised.

It was a little white cute bug, easy to handle. I drove directly from Champagne to Macon where I stayed with my family. Since I left in 1964, I had really lost my contact with all the local people.

When I returned, I was disappointed with the wines. Most of the growers were now selling to the co-op, and the wines were poor. My aunt had retired, and the farmer had retired, and she was paid to pull out her vines. I realized finding small local producers might not be as easy as I thought.

Then I decided to go to the southern Rhône. I had no connection, but I was given the name of a small hotel with a dozen rooms and a restaurant open for lunch and dinner. I went for lunch. Juliette, the owner, was a very imposing woman, she took my order, and asked what I would like to drink. I asked for a Côtes du Rhone blanc, and she brought me a bottle of Château Fonsalette Blanc, and it was fantastic. I asked about it.

“Don’t you know Château Rayas?” she said. “He makes the best Châteauneuf-du-Pape.”

I asked if she could give me the address, and she not only gave me the address, she gave me specific directions. It still took me 90 minutes to find it.

At 4 o’clock in the afternoon I walked down the driveway to a typical rectangular home. I knocked on the door, and an elderly lady told me, “Mister Reynaud is having a siesta, you have to wait.” So I waited. A trucker came by to make a delivery of something and so we sat under these big plane trees together.

After a while, Mister Reynaud came out and I was surprised. He was very small, very trim, wearing a small waistcoat and a beret with gold-rimmed glasses. He looked like a lawyer or librarian. We walked back up to the winery. He had wine glasses that had lost their bases hanging upside down on pegs. There were holes in the walls. This place was not spotless. He opened a huge wooden door with a big ring of keys and in the big cave I could see wines stacked up to the ceiling. He came back with a bottle of 1959 rouge. He opened it and poured the wine in my glass.

I was speechless. I was in shock. These wines were so beautiful.

“Oh God,” I thought to myself, “this is amazing.”

Then he went to the other cave and got me a taste of the ’61.

I told him I would like to take 25 cases of each wine, and asked the price. They were 12.5 Francs, and at the time there were 5 Francs per dollar, so about $2.50 per bottle. I put in my order.

I was prepared. I showed him the importer label, and I knew who was going to pick up the wine. He trusted me implicitly. He didn’t ask for a down payment. We shook hands. That was it.

So I returned and told Hillebrand about my purchases, and his mouth was open in shock.

He said, “You are out of your mind! The retail price of a good Chateauneuf-du-Pape is $2.50 per bottle! You’re going to have to sell these for $5 per bottle, which is an outrageous price. If you can’t sell it, I’m telling you right now, you’re going to have to pay for it yourself.”

I wrote a newsletter and sent it to all the doctors and lawyers I had met through my husband.

Boom. I sold my wine.

Discovering Mister Jayer

Eventually, Martine would strike out on her own and start her own import business, called simply, Martine’s Wines, which she owned and ran from 1979 until she sold it in 2012. The business is lovingly maintained and run today by her friend Greg Castells.

In 1972, it was a difficult year, and red Burgundy got bad reviews from the press. When Paul Pillot came in 1973, he called me from San Francisco because he had one afternoon free and asked if he and his wife could come visit

“I have a vigneron with me and he’s by himself,” he said. “Can I bring him over?”

That was fine with me, and soon after arrived Paul and his wife, and Henri Jayer. We all sat together. The Pillots were yakking away, and Jayer gave me his card and said, “Next time you come to France, I would like you to visit me.”

Jayer was a very quiet man, always smiling, not the excitable type like Pillot. He was very charming, very gentleman-like.

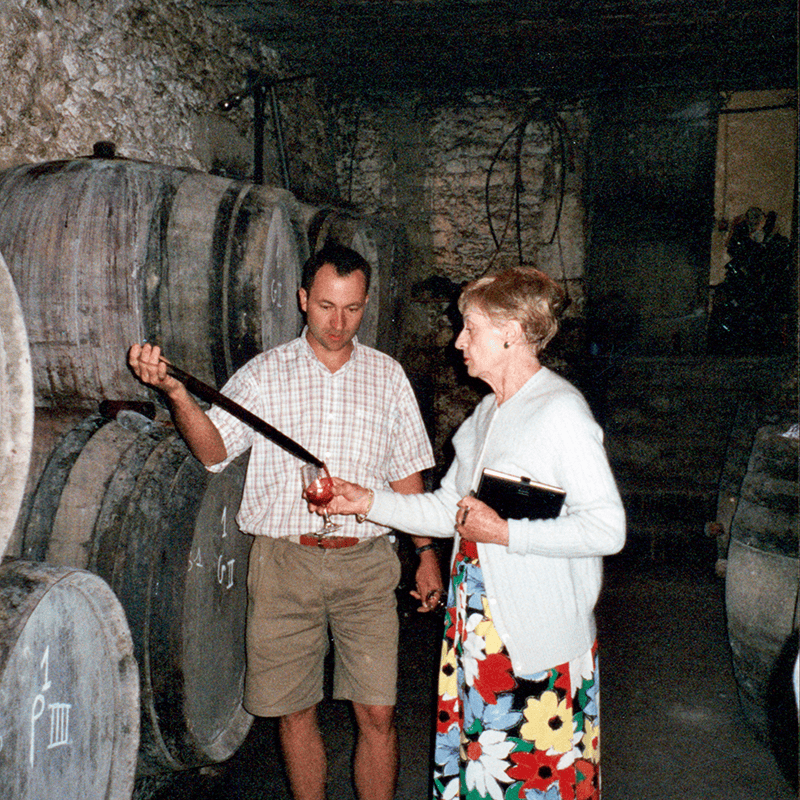

The next year in ’74 I made my first visit. I came in, he gave me a glass and we started barrel tasting the 1973 vintage: Borgougne. Nuits St. George, Vosne Romanée, Eschezeaux. The wines, of course, were superb.

“But look,” he said, “I have this wall full of cases of 1972. The British didn’t buy my 72s because of the bad reviews.”

I said, “I can I try. I’ll buy Bonne Marres, Beaumonts, 3 or 4 wines.”

These wines were not distributed wholesale, so I sold them direct. Immediately every one of my customers loved the wines. From the 1972 vintage on, I sold every vintage from Henri, including the 1977, which was another bad year. But trust me, Jayer never made a bad wine in his life. He taught me a lot about wine, in particular about the dangers of filtration.

I started to tell my other producers, I wanted no filtration of my wines. If you filter the wine, you strip the wine.

Madame Leroy and a Proudly Precise Palate

Maison Leroy was another of the famed producers represented by Martine in the US, helmed by the infamous Lalou Bize-Leroy, known for her imperious personality and mercurial nature.

I didn’t meet Lalou until 1986. I have this friend John who lived in Los Angeles. He was a musician but wrote music for advertising. He made a fortune and was a great wine collector. I organized tastings for him at Jayer, but I didn’t have any introductions to Domaine de la Romanée Conti or Leroy. I had been to DRC twice with some of my producers, but I didn’t have any strong contacts there.

It was May of 1986, I remember, and John was in France and said to me if you’d like join us for a tasting at Maison Leroy you’d be welcome. I said to myself, “Now that’s an opportunity.” I met [Leroy cellarmaster] Toto Rageot at that tasting and he said to me, “You have a very good palate.” I said, “Yes. This is my business.”

“Oh, you import Burgundy?” he said. “Madame is looking for a warehouse. She is displeased with the warehouse at her current importer, the temperature is not correct and she’s worried the wines will not survive. She wants her own warehouse.”

In 1983 I had just moved to San Rafael and I knew there was a warehouse for sale next door. “How big does she need?” I asked. I called my office and asked them to please check it out. Toto asked for my card. I went with John to DRC later that day, and when I stepped in the door, a lady there said, “Madame would like you to call her after the tasting.”

I called Lalou’s office and she said, “I would love to meet with you this week.”

When we met she explained how displeased she was with her situation. I went back to my office—in those days you didn’t have e-mail, we had telex—I sent her a proposal for the warehouse. She bought it, and then she started sending me the quotes for someone to build out the space for her. They were asking $50k.

I said, “You know, I had double this square footage and I spent half of that.” In fact, I did my own installation. So I became her general contractor. I knew exactly where to get everything. She transferred the wine, and when it was all settled she asked me if I could come taste wine with her.

We were in the warehouse with all this Musigny and other great Grand Crus, it was like being in a candy shop. She opened the bottles, checked the corks to make sure they weren’t too dry, and by the end we had about 12 bottles of great wines from the 1940s to the 1960s open.

I said, “Madame Leroy, can we take you out to dinner with these wines?”

“We don’t bring wines to restaurants in France,” she said.

“Here we do,” I said. “Let’s eat French.”

I called Jeremiah Tower to join us and we went to Fleur de Lys. Lalou had a contract with an existing importer, but the next day she called her lawyer and asked him to break the contract, and hired me to represent her.

Lalou is very nice, but she can be… all of a sudden. If you say something she doesn’t like, she doesn’t forget. She knows her mind. You can’t change it. She is very… she is not very diplomatic. She is very straightforward, even sharp around the edges.

So I started selling her wine.

Every year she had a big tasting. If you were invited to lunch, you had a booklet, and a list of the Grands Crus and you had to taste blind and guess which wine is which Grand Cru and what vintage is what. After you make your decisions, mark the wines in the booklet, and write your name, you tear the page and give it to the sommelier.

This was a big affair. Jancis Robinson was there, all the Wine Spectator guys, Pierre Rovani, Matt Kramer, Michel Troisgrois, Paul Bocuse. Maybe 25 people, all seated four to a table. I brought my biggest customer in those days from near St. Louis.

After the tasting, we all have a buffet lunch. I went into the kitchen, and there’s the cellarmaster Toto and André Porcheret who was the winemaker at the time. They’re scoring the ballots. I innocently asked, “How are you progressing with the task?” and they looked up and said, “You’re doing very well.”

I didn’t think anything of it, and left the kitchen. But a little while later, I ran into one of the sommeliers who took me by the hand and said, “Congratulations, you won the tasting!”

I went back to the kitchen asking, “Are you serious?” I was flabbergasted. How could I do that, how could I beat people like Jancis at this game?

So I went to Lalou, and said “Did you know I won the tasting?”

She just walked away. I think she wanted someone more important than me, like Michel Bettane or Jancis or Michael Broadbent to win. There I was, just the importer. I thought OK, OK, but I was so excited for myself. I could not believe I could do that. For me it was like winning a gold medal.

A while later, I ran into Porcheret again and he asked, “Did you get the case of wine that was reserved for the winner?”

I didn’t. Anyway, I have the booklet.

Six months later, my friend sent me a copy of the column about the tasting from Jancis, where she names everyone there but says the person who won the tasting is Martine Saunier. I sent a copy to Lalou and she never answered or acknowledged it. I don’t think she ever forgave me. She is a very peculiar woman. I know she likes me, but she wanted to make a splash with some important person. I beat Bettane and that she wouldn’t forgive.

Martine on Good Wine

Martine built her reputation on some of the wine world’s most vaunted producers, but she sought out great wine throughout France across a wide variety of price points, always with a firm point of view on quality.

The wine I like is the wine that gives me pleasure. When I drink it and I taste it, it’s smooth, it has a beautiful aroma. It comes from grapes. It doesn’t smell like a barnyard, or a little old, or not too clean. Those are the defects you don’t want to have in a wine.

When I was a kid, you know, we made wine very simply. First, the winemaker was the one who took care of the vineyard. Each vine was carefully tended. No one ignored the fact that you had to do the manual work. They plowed with the horses, and put the manure on from the farm. The wife did the pruning.

I remember André Porcheret, who said very clearly to me once, “On my day off, I walk through my vineyards and I look at everything, and I always find something I could change and make better.”

Each vine is special. That is what being a vigneron is all about. Taking care of the vineyard. Good wine can only be made with good grapes, and the grapes come from good plants, that are healthy. You know sometimes they are sickly, and you have to take care of them. Don’t prune too short, don’t prune too long. You don’t want make a lot of grapes but you want to make good grapes. The quality of the grape is the most important. If you have healthy grapes, not too abundant, you are going to make a good wine, especially if you have a good vineyard which means in a nice location.

Let me say that when I was a child, we didn’t do much more than spraying the vine with sulfur to prevent mildew. That was about it. We didn’t add yeast during fermentation, it didn’t exist! We didn’t add sulfites when we made the wine, or when we bottled. You see in those days most of the wineries in Burgundy didn’t bottle except for themselves, and the wine didn’t travel very much. And when they were shipped to England by barrel, it was going to England. It was a cool country and the wine was stuck in a warehouse in Bristol or London. And the negociant would bottle when he felt like it, and when he felt like it was ready to be bottled. That was very simple.

When people talk to me about natural wine, I keep thinking, my aunt’s winery made natural wine, except now we have to put some sulfites for bottling—a very small quantity. Wine is a natural product and a living product. Once it is in the bottle it continues to live and be transformed. And so if you send your wine in the middle of the summer, it is going to ferment or going to cook.

To make a good wine is very, very simple but the winemaker has to have a touch. Let’s face it, not everyone can make good wine. You have to have a sensitivity to your art, and first you need to know how to prune, how to treat your vines—not to exceed a quantity of grapes, whether it is red or white. That is the reason why it is so different from one vineyard to another. In Burgundy, you know we have also these microclimates. What one guy is doing in his vineyard, and what time is he going to harvest is different from the other guy, who has a vineyard up the hill that is cooler, or doesn’t have as much good exposure.

When I left Burgundy in the Fifties is when all the chemicals appeared. Everyone was happy to see that you could spray the vineyard with weed killers so you don’t have to plow, and everyone was happy to see that you treated your vines, so they don’t get any disease, and so everyone put on a lot of chemicals.

And then the association, the Vin de Bourgogne, decided to put on the market a new vine stock that would be higher so you don’t have to bend so low to pick the grapes and that would also produce a higher quantity. All the wineries who decided to do that went wrong, and for a while we had very poor quality of wines in Burgundy. Fortunately, some wise wineries decided not to go for those new things, and stuck with their selection massale.

People ask me what is the difference between a good wine and a great wine? It’s very simple. Or it is simple to me because I have been in touch with a good wine and a great wine. A good wine is simple but healthy—fresh to the palate, not complicated, something you are enjoying with your meal. It can be a good wine anyplace. Either in Beaujolais or Burgundy, probably the plain Burgundy appellation on the flat land does not make a complicated wine.

But if you want a great wine, you have go to a Premier Cru that is more on the hillside, or then the Grand Cru that is really a special vineyard. A special vineyard is not only the climate but also the soil. The complexity of the soil, whether it is a rocky soil, and the exposure, is it southwest or northwest? Anything will do. But the right combination is amazing.

When I started to get really into the market of buying Burgundy, I knew exactly what I wanted. I knew I wanted to trust the winemaker, who had a good sense not to over-treat his vines with chemicals, with the good sense also to have good barrels, a spotless winery, very strict as far as cleanliness. When I began I also had the feeling that some people have a knack, they have a feel, they have a sensibility, they have a passion for what they are doing.

Great winemakers are people with a passion. There is nothing better for them than making wine. It is the reward they have every year at time of harvest when they go and harvest the grapes they have the new challenge. Are they going to make a great wine, is it a great vintage?

Every year is not easy. There are good vintages, bad vintages, medium vintages, but no matter what is the vintage, a great winemaker should never make a bad wine.

Images courtesy of Martine’s Wines.