I’m constantly befuddled by the ads that I get shown on the internet. Most ad networks seem to think I’m a woman, and as a result, I see everything from lingerie to breast pumps in my Facebook feed. You probably won’t believe me, but I swear I don’t have the kind of browsing history that you imagine would lead to such things.

In addition to the head-scratching ads for one-piece swimsuits and the latest issue of Elle magazine, I unsurprisingly also happen to get a lot of ads for wine-related stuff. Not that those ads are particularly useful. Most of them are for any number of completely lousy wine clubs, the latest Clean Wine brand, and most recently, for wine investment funds and services.

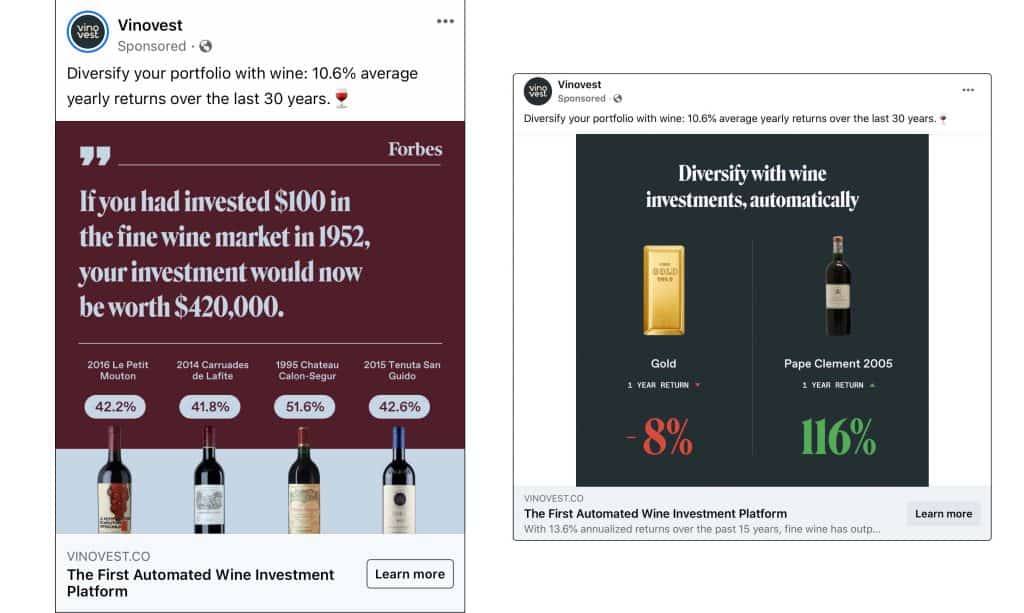

You know that saying about a fool and their money? Look at that ad above on the left. I don’t even understand how it’s legal for them to say that. It is 100% bullshit. Just a straight-up, complete pants-load falsehood of the most epic proportions.

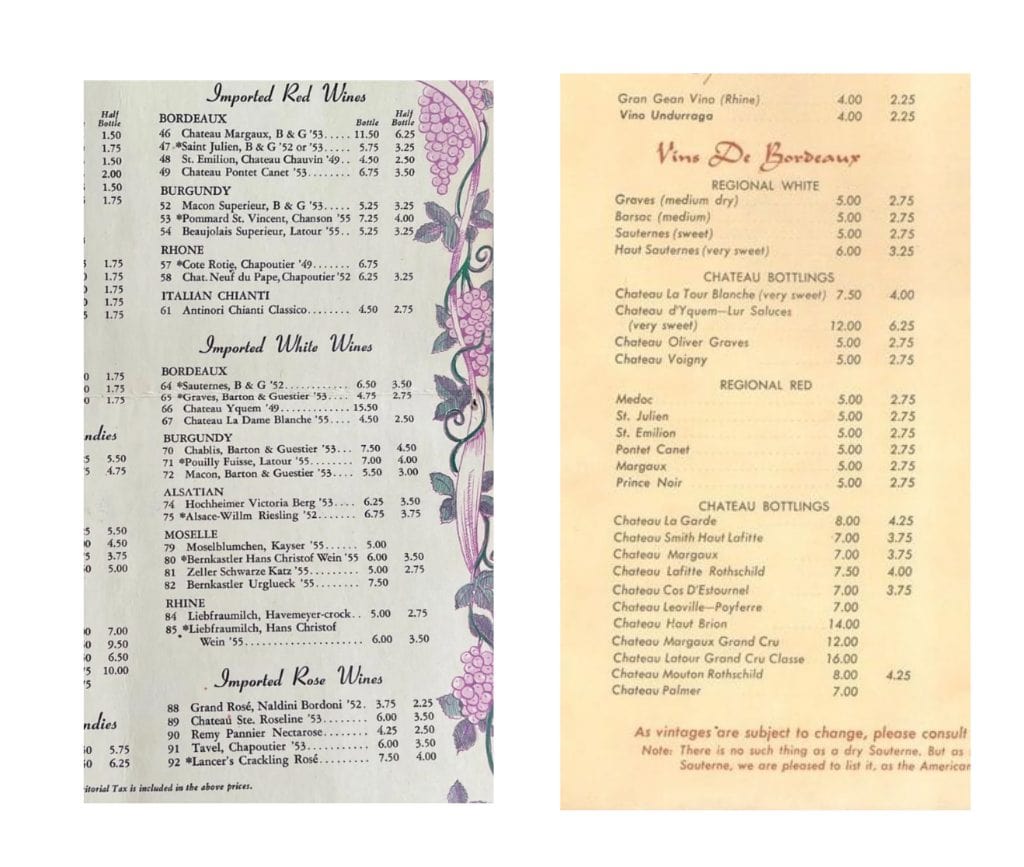

Let’s take a look at that claim, shall we? In 1952, Chateau Latour was selling for about $16 a bottle on restaurant menus. That means you could probably get it for less in a wine store. You can see some of the prices for top Bordeaux wines below on these two mid-50s wine lists, especially the one on the right from Arnauds in New Orleans. Bottle prices are in the left of the two columns.

So how would you have invested in $100 wine in 1952, if you wanted to? You’d have bought 10 bottles of (the excellent) 1949 Chateau Latour. Let’s make the exercise easy and say you bought an entire wooden case of Chateau Latour, and never removed the bottles from that case, storing it impeccably in your family wine cellar ever since.

If you wanted to then sell that set of ’49 Latour OWC today, how much do you think you’d get for it? Vinovest wants you to believe you’d get $420,000.

Well, for starters, I can go online and buy a bottle of 1949 Latour for between $3300 and $7400.

But of course, pristine bottles sold at auction will fetch more. How much more? I’m not sure, but let’s put it in perspective this way. A full case of 1961 Latour, the Bordeaux vintage of the century, the so-called “holy grail” for collectors recently sold at auction for $56,615. Is that a hefty return on your $100? For sure. But $420,000 it most certainly is not.

If you had bought a lot of Bordeaux and Burgundy in the 70s and 80s you’d definitely be sitting pretty right now. Of course, that’s true of real estate, Rolex watches, and baseball cards, too. If you got in early, you’re quite lucky.

But let’s be clear, these wine investment people are deliberately confusing physical asset appreciation and compound interest. When you invest $100 in wine, you don’t get annual returns that you get to reinvest. You get whatever that wine is worth when you decide to sell it.

The Vinovest folks are using math that looks like 15% annual returns on an initial $100 investment over 60 years. Never mind the fact that their own ads advertise annual returns of (only) about 10.6%. Never mind the fact that few people invest in a 60 year timeframe. Never mind that if I depended on a 60 year timeframe I’d be dead before I realized my investment returns, and that the majority of the returns in a scenario like that come in the last few years. Also, the difference between a 15% annual return over 60 years and a (“we didn’t do quite as well as we thought) 13% return is $300,000 less money. Remember that for 2 more paragraphs.

These days buying blue-chip, investment-grade wines is the playground of the uber-wealthy. The wines that actually have decent track records of price growth cost $800-$8000 per bottle. And if you’re going to really buy those bottles (presuming you can get your hands on them) you’re gonna have to pay to store them (securely, with climate control) until you’re ready to sell. And all the while hope that you don’t become the victim of the hundreds of organized crime rings out to steal your assets.

Presumably that’s where outfits like Vinovest want you to believe they’re helping you out. They’ll take care of all the logistics for you, and maybe even allow you to buy wine fractionally so that you can invest $10k or $50k and have a slice of a portfolio that includes a whole bunch of wines, not just the 4 bottles of Petrus that your investment money might get you.

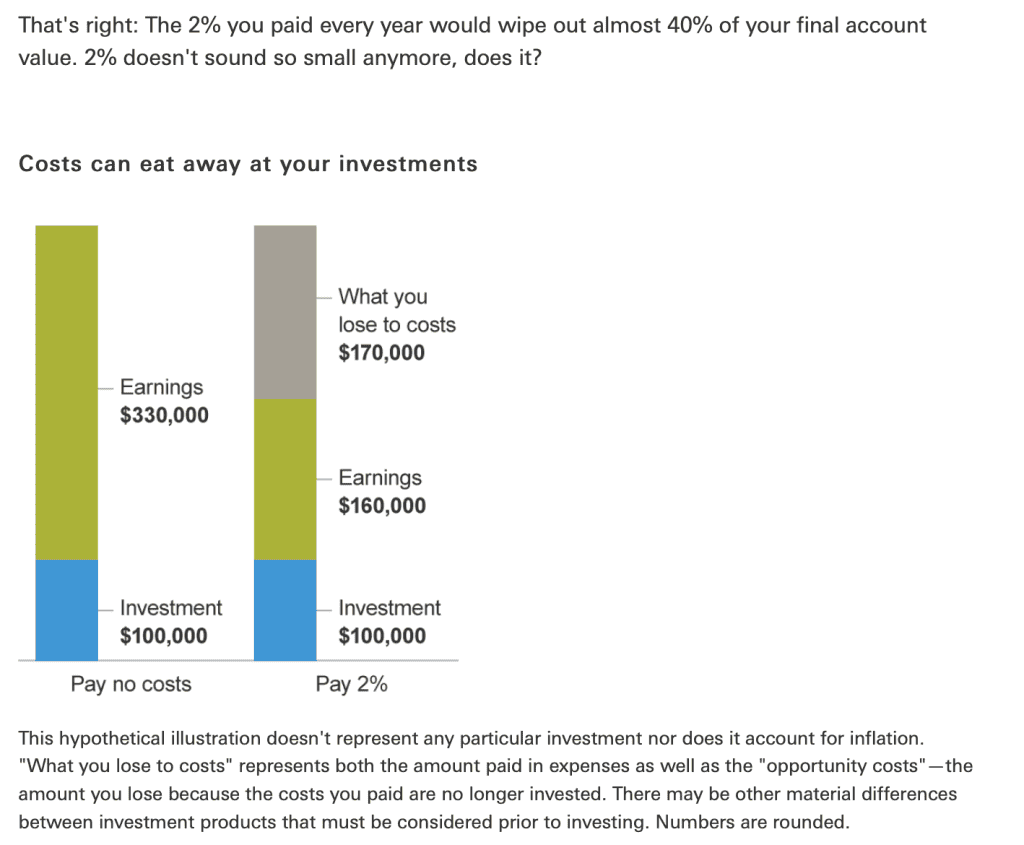

There’s just this little matter of their 2.5%-2.85% annual fee.

Fees in the investment world are evil. Just ask any fiduciary whether you ought to be buying a mutual fund with a 2.5% management fee or a no-fee ETF Index Fund to invest for retirement.

I’m no fiduciary but here’s the numbers: if you invest $50,000 with a service that charges you a 2.5% annual management fee, and hold that investment for 20 years, with 10% annual returns, you’d have $212,392. If you hadn’t paid the fee, you’d have $336,365.

That’s right. You’re going to lose somewhere between 22 and 37% of your possible accumulated wealth just for the privilege of holding that investment. It’s a great deal isn’t it? For the person who’s charging the fee.

It’s not a great deal at all. It’s idiotic. But don’t take it from me. Listen to Vanguard Investments.

Of course, the sneaky wine investment people will say something along the lines of “but our returns are so high, that fee makes less of a difference” but that’s also not true. Because you know what? You pay 2.5% of your account’s value every year. So when it grows a lot, you’re paying 2.5% of that bigger number.

Fees are evil. Fees are stupid. And so is investing in wine.

If you’re rich and can buy big wooden cases of First Growths and DRC en primeur, then you should definitely do that. But otherwise, you shouldn’t bother.

And you 10000% should not pay fees to some service that lies about how much money you could have made if you were invested in wine, implying that you could make lots if you give your money to them.

Anyone who has less than a $10 million net worth should listen to billionaire investor Warren Buffett’s advice. Which boils down to putting your retirement money in no-load index funds and forgetting about it.

Then you might end up with enough money to buy a few nice bottles of wine to enjoy in your retirement.