Winemaker Thibaud Boudignon looks me straight in the eye and says, “I want fresh vitality in my wines and an almost brutal minerality,” and I honestly have to catch my breath for a moment, since it’s been some time since anyone spoke to me so directly in my love language.

I gulp and take another sip of his electrically bright Chenin Blanc and concentrate on scribbling notes in my notebook, all the while thinking that I can’t imagine a better description for the kinds of white wines that I find most arresting.

I can say without question that Boudignon’s efforts are, in fact, truly arresting. This young man, a relative newcomer to the tiny Loire appellation of Savennenièrs, is setting a new standard for what Savennenièrs can be.

Boudignon never set out to be a winemaker. In fact, what he wanted more than anything was to be an Olympic champion in Judo. With his bearded, muscled frame and massive hands, Boudignon certainly looks like he’d make a formidable opponent in any contest of strength, but dreams and reality don’t always match up.

“By the time I was 21 I realized I was never going to be a champion,” says Boudignon with a shrug, “so I headed to the south of France to get some work.”

Boudignon, who lost his mother Françoise when he was only 17, had spent some of his childhood playing in his paternal grandfather’s vineyards in the South of France, and also grew up in Bordeaux drinking Medoc wines at lunchtime with his mother’s father, François.

So when he headed south, he naturally fell into work first in the vineyards, and then in the cellar. Boudignon would eventually make his way to Bordeaux, where he worked at Château Olivier and Château Canon-la-Gaffelière, and then to Australia where he worked at De Bortoli, followed by a stint at Domaine Charlopin-Parizot in Gevrey-Chambertin.

“Eventually I arrived in the Loire, where I was put in charge of Chateau Soucherie,” says Boudignon, who arrived at that Savennières producer in 2007 and soon after realized that he and the estate’s owners had a different vision for where the wines should go.

“I decided in 2009 that I needed to work for myself,” says Boudignon, “but I knew I needed to have money to start something. I stopped being an employee in 2015, worked as a consultant until 2018, and since 2018, I have been focused only on my production.”

A Blanc Slate

After making that fateful decision in 2009, Boudignon began buying grapes in Anjou to make roughly 3000 bottles of Anjou blanc.

“I had three barrels that all tasted different in that first vintage, and I decided to blend them and make it a tribute,” says Boudignon, describing the creation of the Anjou Blanc he named ‘a François(e).’

“When you decide to write your mother and your grandfather’s name on the bottle, you don’t cheat on quality,” he says.

That wine would go on to win Boudignon his first notable acclaim as a vigneron and was snapped up by top restaurants across France. Boudignon took the money he received and reinvested it in his operation, something he has been doing ever since.

Within a couple of years, Boudignon had begun sourcing small amounts of Savennières, prompting him to learn as much as he could about the appellation.

“Do you know that there are roughly 300 hectares of land in Savennières, but only half are planted?” he asks. “I began to think to myself, ‘I wonder what the potential is here?'”

As he was doing research on the appellation, he came across an old reference to a walled vineyard named Clos de la Hutte. “I said to myself ‘where is this place?’ and I began to search.”

Resurrecting a Clos

He would eventually find the wall, but it no longer surrounded a vineyard. So Boudignon used the majority of his savings to buy the land and put a vineyard back in what he is convinced was one of Savennières’ historically significant lieux-dits, or named vineyard sites.

He got his first harvest off the vineyard in 2015.

“Clos de la Hutte is the culmination of everything I’ve done,” says Boudignon. “It is our grand cru, and it is always a monster. Whatever the year, what it produces is unbelievable. It is not impressive but it has power. It is like the gentle swipe of a tiger’s paw. He is not punching you, but you feel the power.”

Like most of Savenniéres, the six acres (2.5 ha) of Clos de la Hutte consists of shallow topsoil of light clay chock full of bits of the fractured dark schist (known locally as Anjou Noir) that sits beneath it.

This schist represents the metamorphic remains of something called the Amorican Massif, what was once a large Paleozoic mountain range that has been ground down to nearly nothing in the roughly 300 million years since. But the roots of this mountain range remain, offering up the sparkly, flaky rock of their buckled and compressed foundations as places for vines to grow.

These rocky shallow schist soils are the defining characteristic of the Savennières appellation, which is planted almost exclusively to Chenin Blanc (though there are some secret pockets of Verdelho, which is a tale for another time).

Investing In a Legacy

Continuing with his theme of reinvestment, Boudignon built himself a small winery in 2016 to exacting specifications, heavily focused on maintaining conditions in the cellar while keeping the carbon footprint of his operation to a minimum. Because the winery sits on the same schist bedrock as his vineyards, Boudignon couldn’t dig an underground cellar and has settled for a custom system that pulls ambient air into a buried pipe to reduce the energy required to cool it as well as allow precise control of humidity.

Boudignon has structured the building to require what he sees as the absolute minimum of handling from fruit to bottle. “I want to take 100% of the potential of the vines and put that into the wine,” explains Boudignon. “As soon as you cut the grapes you are losing potential. That is why I invested so much in this winery.”

Boudignon works biodynamically but seems content to dispense with all the dogma associated with the approach.

“When Steiner was looking at biodynamics it was about yield and quality, but really, biodynamics is about life,” says Boudignon. “For us, the vineyard is the most important thing. My goal is a healthy vineyard without stress, where the grapes can reach complete maturity. I like relaxed fruit. When the vines suffer things get out of balance.”

“It’s not just the grapes you want relaxed,” says Boudignon, “It’s also about the team. We respect the soil, but we also respect the people we work with, it’s an entire system. These kinds of wines are possible because of the work we all do in the vineyard.”

Boudignon does no analysis of his grapes or his wines through the winemaking process, choosing instead to pick when he thinks things are ripe, which for him is mature but not overripe. He assiduously avoids botrytis, which he believes makes the wine much more prone to oxidation.

Like many winemakers, Boudignon believes the single most important decision he makes every year is when to pick, a moment that is informed by his desire to express everything that his schist soils are capable of showing.

In Service of Minerality, In Search of Emotion

“Since 2018, all I do is eat, think, and sleep Chenin,” says Boudignon, “and the wines have started to be different.”

“I don’t want to produce a wine that has a lot of flavor,” he goes on to explain. “I want a wine that might sometimes be closed when it is young, but which ages well and more than anything else, expresses minerality. Minerality is key.”

“I don’t want the wine necessarily to be impressive on the table,” he continues, “I want the wine to keep the mouth fresh, to make me want to drink and want to eat. Acidity, yes of course, but also minerality. There is a difference. Acidity is vertical. Minerality is ongoing. It pushes and makes the wine long. These days it’s trendy to be focused on pH and numbers, but I don’t believe you can see minerality in terms of a number. You can see minerality when you walk through the vineyard and look at the fruit.”

Boudignon prefers to harvest as quickly as possible, and get the fruit into the cellar as cool as possible. He presses whole clusters into steel tanks chilled to 37˚F/3˚C, and then moves some of the wine to old oak barrels (and recently some concrete eggs) for fermentation with ambient yeasts. He likes to let the wine do its own thing in the cellar, though he prefers to inhibit malolactic conversion, keeping as much acidity in his wines as possible.

“I haven’t done malolactic fermentation since the beginning,” says Boudignon. “The Chenin I like doesn’t have malo, and I want to make the wines I like to drink. I think a lot of people pick too early to preserve the acidity they lose during malo, and they aren’t getting full maturity. We keep things cold and then add sulfur in February or March. If the wine happens to go through malo, it’s not a big thing,” he shrugs.

The wines are never fined or filtered.

“I work for the taste,” continues Boudignon, “For the emotion of the thing. I am not afraid of what will happen. It’s like when you are in love with a girl. If you spend all the time being afraid that she will leave you for someone else, you can never really be with her. Maybe I’ll make mistakes, but mistakes are a part of the winemaking process. To make a mistake is not a problem. To keep making the same mistake, that is the problem. I learn from each vintage, and now I have the capacity to see what will happen.”

Farming in the Face of Disaster

From the 18-or-so acres (7.5 ha) he farms, Boudignon produces roughly 3000 cases of wine each year, all Chenin Blanc with the exception of a tiny amount of rosé.

That is when he gets a harvest at all.

In 2017, he and many fellow growers lost their entire crops to frost and hail. In 2019, he harvested merely 30% of his normal yield.

“When you go into your vineyard and see it all destroyed, it is like a bomb going off—in your vineyard and in your mind,” he says. “That is why I had to invest in frost protection. If I cannot protect my young vines, I think I should just stop doing this.”

Boudignon spent 30,000 Euros last year for an electronic frost protection system—a wire that runs along the length of each cordon that emits enough warmth when turned on to keep young spring buds and leaves from freezing. It’s not foolproof, but he showed me tender young leaves that were still clinging to life on vines that had the wires and desiccated dead leaves on those that didn’t.

Boudignon has planted his vineyards with 10 different massale selections of Chenin Blanc, some from Domaine Huet in Vouvray, and others from elsewhere around Savennières. Most of the vines are trained in the guyot-poussard method, a bi-lateral pruning that supposedly increases sap flow and prevents vine disease, but which Boudignon likens to training a bonsai.

In Clos de la Hutte he has also planted half an acre of his vines on their own roots, rather than using rootstock, in an experimental search for more mineral expression.

“I just wanted to see what the difference would be,” says Boudignon, who has started bottling those vines separately, as they do indeed express themselves differently.

Boudignon has also recently begun a new vineyard project in another walled site just down the road from Clos de la Hutte, in a sunnier, windier spot with more sand and even less soil between the sunlight and the schist. These 4.5 acres (2 ha) will be known as Clos de Vandleger.

Anticipating Greatness

At 40 years old, Boudignon is entering the prime of his winemaking career, having already turned many heads. Indeed, his success as a young vigneron has brought renewed attention to the Savennières appellation, which he has mixed feelings about.

“People are arriving now in the wine business with Instagram and a lot of money,” he says with a shake of his head. “We have our 7 hectares and we are simply focused on nothing else but quality.”

Boudignon is pleased that he has gotten to the point where the economic pressure to make sales and support the business can take a back seat to the wines and his sense of what they need to show their best.

“Now I can say that people will not taste the wines until they are right,” he says proudly. “It is a responsibility rather than a pressure now.”

Right for Boudignon seems to mean chiseled wines, with resonant complexity, incredible expressiveness, and mouthwatering brightness. And yes, a more than an occasional dose of brutal minerality.

Please sir, may I have some more?

“When you are young,” says Boudignon, “You think having experience is something that older people hold over you like it helps them to say that they are important. But when you get older you realize experience is important for understanding, to anticipate. I am not living in fear. When you start your life in sport, you realize your career is very short. The same in wine. Maybe at the end of my life, I will have only 20 or 30 vintages. I don’t want to regret something. That is why I do everything with 100% passion and 100% investment. Everyone will tell you they want to produce the best wine possible, but the question is what do they do in the service of that? What you do is what makes the difference, every moment that you are ready to do what you have to do to get the kind of wine you believe in. When I do that, this doesn’t feel like work at all. In fact, when I do that, everything makes perfect sense.”

Tasting Notes

I don’t think I can recommend these wines highly enough. They now are among my absolute favorite renditions of Chenin Blanc.

In addition to the wines below, Boudignon makes a rosé, which he did not have available to taste when I visited, and which I am quite keen to try. Keep an eye out for it.

2020 Thibaud Boudignon Anjou Blanc, Loire Valley, France

Pale gold in the glass, this wine smells of lemon oil, quince, and flowers. In the mouth, explosive acidity offers lemon and grapefruit flavors tinged with acacia blossom and a bit of quince and pear. Mouthwatering, fantastic crushed stone minerality. 12.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $45. click to buy.

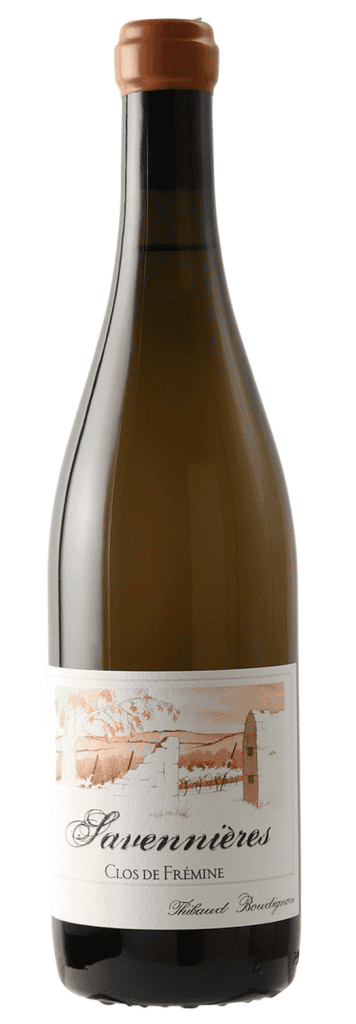

2020 Thibaud Boudignon “Clos de Frémine” Savenniéres, Loire Valley, France

Pale gold in the glass, this wine smells of flowers, lemon oil, wet stones, and a hint of guava. In the mouth, bright juicy lemon, white flowers, and acacia blossoms all swirl with a silky texture and slightly softer acidity. This wine is detailed, deeply stony, clean, and bright with a long finish. Gorgeous. Aged in 600-liter barrels, with a total of about 10% new oak. 12.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $85. click to buy.

2020 Thibaud Boudignon “a François(e)” Anjou Blanc, Loire Valley, France

Pale gold in color, this wine smells of wet stones and lemon pith with a hint of unripe pear. In the mouth, silky flavors of lemon and a hint of banana mix with pear and beautifully chiseled acidity. Gorgeous lemon pith and lemon oil flavors emerge with hints of flowers that linger in the finish. Silky texture and beautifully saline. This is now a selection of only free-run juice and only the best fruit from the La Gare vineyard from which Boudignon sources his Anjou Blanc. Sees 20% new oak. 13% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $75. click to buy.

2020 Thibaud Boudignon “La Vigne Cendree” Savenniéres, Loire Valley, France

Palest gold in the glass, this wine smells of quince and lemon pith. In the mouth, silky flavors of lemon pith, pear, grapefruit, and lemongrass have a fantastic juicy brightness. The wine features a long, stony finish with a hint of a chalky texture. Deeply mineral. This wine comes from a 1-acre parcel of vines that Boudignon has contracted. No new oak used. 12.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $95. click to buy.

2020 Thibaud Boudignon “Clos de la Hutte” Savenniéres, Loire Valley, France

Pale gold in the glass, this wine smells of wet stone, tree blossoms, lemon pith, and grapefruit. In the mouth, incredibly silky flavors of lemon pith, lemon oil, unripe pear, acacia blossom, and quince have a cistern-like minerality with deep stony depths. Incredible acidity, great length. One of the best mouthfuls of Chenin Blanc I have had in a long time. This wine ages in 30% new oak of various sizes for 18 months before spending another year in the bottle before release. 12.5% alcohol. Score: between 9.5 and 10. Cost: $110. click to buy.

2020 Thibaud Boudignon “Clos de la Hutte – Franc de Pied” Savenniéres, Loire Valley, France

Palest gold in the glass, this wine smells of lemon pith and wet stone. In the mouth, gorgeous stony lemon and grapefruit pith flavors are silky and deeply stony. Essential, stripped down, and ethereal, with some hint of greengage plum along with citrus and unripe pear. Stony, stony, stony. This is a special bottling made from only own-rooted vines planted in the stoniest sections of the Clos de la Hutte vineyard. The wine is aged in glass demijohns, “to go straight to the minerality,” says Boudignon. Only 300 bottles are made. 11.5% alcohol. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $??