Can you taste integrity? Spend enough time thinking and talking about wine, especially great wine, and inevitably you have to move beyond the merely tangible. Wine is more than just geology, chemistry, and botany. Like any human craft, honed over lifetimes and generations, it begins to contain something of us, to reflect something of the human spirit behind it.

All of which is why my answer to my opening question is unquestionably yes, just as you can taste honesty or love in the bottle as well. Sometimes subtle, sometimes electric and deeply powerful, the sensation of these (things? forces? principles? ideas? energies?) isn’t extremely common in my experience, even for those who drink selectively with deliberation and care. Their perception in wine, like a psychedelic experience, depends heavily on set and setting. We easily bring as much to wine as we get from it.

I recently got a deliciously heavy dose of bottled integrity on my visit to the Savoie region of France. On a crystalline-bright morning, I found myself wandering one of the more remarkable vineyard sites I have ever visited, listening to a very young man speaking (and acting, and farming, and winemaking) with a level of conviction and vision that are rare in winemakers twice his age.

On every wine trip I take, I hope to encounter at least one producer whose story and wines make the whole trip worthwhile. My visit to Domaine Curtet, was definitely one of those moments.

Florian Curtet hasn’t been in the world of wine for long. At a mere 30 years of age, he’s basically just a few years out of school. A local Savoyard, originally from Annecy, he studied enology in Beaune before returning to Annecy to continue his studies of Agriculture, in part with an internship that found him working with the well-known organic producer Jacques Maillet.

Maillet was good friends with fellow Savoie producer Gilles Berlioz and with different harvest dates between their estates, Berlioz and Maillet were in the habit of helping each other out occasionally during harvest. One day Berlioz brought with him a young woman named Marie who had recently come to two important realizations. The first was that she wanted to make a life for herself in wine. The second was that the Savoie was where she wanted to make her home. And after meeting the young man working alongside Maillet, she would soon come to a third realization.

As they say, one thing led to another. Florian and Marie fell in love, and George Maillet decided he wanted to retire. Lacking any interested heirs, Maillet asked Curtet if he wanted to take over his property. Being handed 12.3 acres of perhaps the most immaculate organic vineyards in the area was more than fortuitous for the Curtets, who leaped at the chance to pursue their dream of a domaine to call their own.

Their first vintage was 2016, the same year their first child, Lily was born.

Both Florian and Marie believe strongly in their approach to winemaking and winegrowing, which is remarkably clear-sighted and unique, given their youth.

The Forest Vine

Curtet believes strongly in the synergy between grapevines and their surrounding ecosystem. Having purchased a set of what most people would have considered pristine organic vineyards, he is busy returning them as close as is practically possible to what he believes is their natural state. But instead of anchoring on the concept of a holistic farm with animals, plants, and people working without outside inputs (as biodynamics often does), Curtet chooses to focus instead on something that might best be described as… wilderness.

“My philosophy is not organic or biodynamic,” explains Curtet. “It is the philosophy of the green place. Green is carbon, it’s nurturing the soil. If you nurture the soil, you will have good fruit. My work begins with and continues constantly to understand how nature functions. It’s important to see how a forest [ecosystem] functions, and when you see that, you realize that agriculture, as we practice it now, is crazy. It’s the opposite of the forest. In the forest, you have leaves and branches and plants all falling to the earth and it’s never turned over. You see the fertility, you smell the mushrooms. The soil is dark. It is soft. The soil of the [average] farm is not like this, it is very poor, and yet we’re eating this poor fertility all around the world. Geology doesn’t create soil, vegetation does.”

I started by doing the opposite of what I was taught in school.

Curtet prunes during the winter, but other than that, he does no canopy management. Not content to have his vineyards merely surrounded by trees, Curtet has planted hundreds of trees in between the rows of his vines, around and among which he expects his vines to eventually climb and twine. In the meantime, he’s cobbled together branches in places to make what can only be described as arbors that he hopes the vines will climb. The vines are encouraged to sprawl, creep, and flop to the point that they can be difficult to distinguish from the chest-high mix of cover crops that populate the rows. He plans to keep the fruit in the 3- to 6-foot zone, while letting the vines wander where they will, fulfilling what he says is his obligation to let the plant express itself.

“For me, it is important each year to produce and protect a lot of leaves,” says Curtet. “The field must be green. Green is diversity, a sign of life, energy, and growth. Green means roots are at work down in the soil, which will bring balance to the grape.”

When I ask him where these ideas came from he shrugs. “I started by doing the opposite of what I was taught in school,” he says. “I tried to do it my own way. No one told me or taught me to do this. I read some books, I visited some organizations, went to visit some winemakers some farms who were doing things differently.”

“It’s all about how you think,” he continues. “For me, plants, if you respect them, they will respect you. If you understand nature, you don’t have problems. But in school, they teach you that you will have problems, and then you come up with expensive solutions. School, for me, was not objective. Schools depend upon the money of the people who are selling you products or the tractor. There are forces at work there that are about harnessing people into a commercial culture, making them slaves of that culture.”

A Personal Vision

Standing in Curtet’s vineyards, it’s a little hard not to feel a sense of joy and delight, perhaps not unlike watching a group of very young children at play with their imaginations and nothing more than the random items they find around them. The vines and their surrounding vegetation are bursting with life and simply doing what they do, blissfully growing as best they know how. Not being particularly given to mystical, metaphysical, or spiritual expressions, I nonetheless can’t deny the vibrant energy evidenced by the riot of green life on display.

Dry farming is, like many places in France, de rigueur in the Savoie, and surrounding vegetation plays a key role for Curtet in ensuring his vines have enough to drink throughout the year on his unusual (for the Savoie, which is mostly limestone and glacial till) decomposed sandstone soils.

Things have become very commercial, and now there’s an industrial organic culture, where basically all you have to do is not use systemic pesticides or herbicides and you qualify

“Plants create moisture,” says Curtet. “Without vegetation, there is no morning dew. You don’t have water returning from the air to the soil. Trees also pull water up from into the shallower parts of the soil, nurturing plants with shallower root systems. I believe most water problems in the vineyard can be fixed with vegetation.”

Curtet farms roughly what might be considered biodynamically, with no herbicides or pesticides, and up until recently he has maintained his Organic/Bio and Demeter certifications as a way of generally signaling what his wines are all about. But with the coming vintage, he says he has decided to drop the Demeter certification.

“These labels and certifications are less and less restrictive these days,” he says. “Things have become very commercial, and now there’s an industrial organic culture, where basically all you have to do is not use systemic pesticides or herbicides and you qualify. And now with biodynamics, Demeter says they want a farm to be autonymous but then they allow people to buy treatments from outside. If you’re biodynamic, for instance, you can go in the vineyard with a tractor whenever you want. It’s crazy. I don’t respect this philosophy, so I don’t use the name biodynamics anymore.”

Interestingly, Curtet doesn’t believe in compost piles, which he says heat up to the point that it kills some of the life within the compost.

“They’re sterilizing life,” he says, “if you’re putting that compost on the vineyard then you’re putting something not very dynamic in the soil.”

Place Not Variety

In the two vineyard plots that he works, Curtet has planted or grafted a massale selection of Jacquere that he has gathered from what he considers all the best sites in the Savoie, along with a number of other white varieties including Gringet, Altesse, Mondeuse Blanche, Molette, and Savagnin, many of which will be harvested for the first time in 2021. These are all planted in a 7.4-acre vineyard named Le Cellier des Pauvres (The Cellar of the Poor). In a 4.9 acre vineyard named Les Vignes de Seigneur (The Vineyard of the Lord), he also has some very old Mondeuse (a number of vines more than 100 years old) as well as Gamay and Pinot Noir.

Curtet says that at some point he’s interested in farming all the immediate genetic relatives of Mondeuse, as if there’s something about having a complete family tree growing in one place that provides a sense of completeness and harmony. At the moment, the scientific jury is still out as to whether Mondeuse Noir is the child or the parent of Mondeuse Blanche.

Despite making several single-varietal bottlings in his first few vintages, Curtet says he has decided to make only two wines moving forward, a white field blend (he feels confident harvesting all his white varieties simultaneously and co-fermenting them) and a red blend assembled after fermentation (as Mondeuse and Gamay ripen at very different times).

Curtet says he never plans to make more than the roughly 2000-2500 cases he produces each year, though some of the trees that he has planted in the vineyards are heritage apples, and he has plans to make cider, in part a nod to his wife’s Brittany heritage.

Simple but not Natural

When it comes to winemaking, “I don’t use any artifice in the cellar,” says Curtet. “I only use sulfites at bottling. I don’t want mouse [taint], it tends to make customers not happy.”

Curtet ferments with whole clusters (preferring what he says is a slower, “less dynamic” fermentation that way) and ambient yeasts in large concrete tanks, where the wines age without racking until they are ready for bottling.

“I don’t have oak, I don’t want oak,” says Curtet. “I want the expression of soil and grape, not the ‘style’ of oak. I prefer the wine to live in larger volumes, too. I think it produces more harmony, diversity, and balance.”

For purely economic reasons, Curtet’s first few vintages have aged for only 9 months in tank on the lees, but Curtet says he will be moving to 18 months of elevage soon, as he feels two winters in the cellar will make the wines “more finished.”

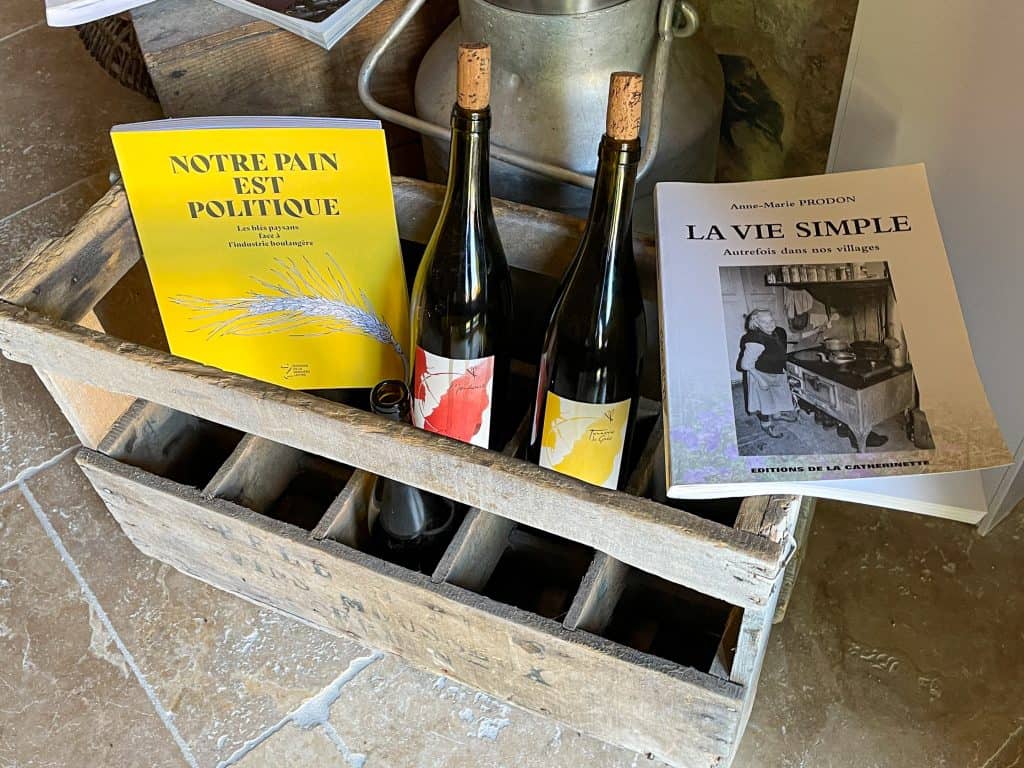

At first, Curtet was making his wines in a rented facility while keeping his eye out for a property reasonably close to his vineyards. A couple of years ago, he spotted one, and now he and Marie have a small farm in the town of Châteaufort where they have built a modestly functional winery, remodeled a stone cellar into a little tasting room, and are busy rebuilding an old farmhouse for their family to live in.

Small is Beautiful

“Our philosophy is to be small,” says Curtet. “If you are big, you have a lot of people working for you, and you don’t know your own work. My work is to be in the vineyard and in the cellar, to meet my customers or journalists like you. We take time to do that, and to reflect on our system of culture.”

In addition to Florian and Marie, the estate’s workforce consists only of Florian’s sister, who has been working with them for the past couple of years, and an occasional additional harvest hand. While his sister helps out in the vineyards when there is work to be done, Curtet says her main job is to “develop the commerce within 100 kilometers.”

Part of Curtet’s “small” philosophy involves an attempt to sell 50% of his wine close to home. “There’s a lot of carbon and pollution involved in selling farther,” he says. “Now with all the problems in the world we are trying to sell differently in addition to working differently.”

Paying off the Philosophy

I walked the vineyards, explored the cellar, and heard all of this before I had ever had a single sip of Curtet’s wine. And I must say, that when I finally did sit down opposite Florian in the little whitewashed, vaulted stone room they use to welcome guests, I was nervous. After being so impressed with Curtet’s clarity of thought, so dazzled by the vitality of his vineyards, and so charmed by the scale and dedication of his operations, I was dreadfully scared that the wines might not measure up. Or simply that they might not be to my taste.

But I am happy to say that they both handsomely paid off my anticipation while deepening my appreciation for Curtet’s vision. Were they the most amazing wines that I tasted while in the Savoie? No. But they were really damn good. And as an expression of Curtet’s ideas and skill they were an incredible beacon suggesting possibly profound things to come from this little family estate.

I’ll put it bluntly. I don’t think I’ve met 30-year-old vigneron with more promise or conviction in my life, and I can’t wait to see what Curtet and his wife will have managed to produce in 10 years, when their vineyards look more like wild orchards, and his new plantings have some more complexity that comes with maturity.

Mark my words, this is just the beginning of something truly great. And if, indeed, you want to know what integrity tastes like, just go find yourself a bottle of Domaine Curtet.

Tasting Notes

2019 Domaine Curtet “Tonnere de Gris” White Blend, Savoie, France

Pale gold in the glass, this wine smells of apples and chamomile and bee pollen. In the mouth, bright lemon and apple and grapefruit flavors have an electric, dynamic quality with bee pollen and lemon oil and gorgeous acidity. There’s NOT a heavily mineral core here, which is what you might expect from these grapes grown on limestone. A roughly equal blend of Jacquere and Altesse. 11% alcohol. Tonnere means lightning. Gris refers to the soil. Bottled lightning, indeed. Score: between 9 and 9.5.

2019 Domaine Curtet “Frisson des Cimes” Red Blend, Savoie, France

Medium garnet in the glass, this wine smells of wild berries and herbs, with a floral perfume resembling something like walking through a flower garden in summer. In the mouth, gorgeously bright berries, herbs, and flowers make a seamless whole that is remarkable. Faint, velvety tannins hang in the background and caress the palate while fantastic acidity keeps the berries, herbs, and flowers vibrant and juicy on the palate. A blend of Gamay, Mondeuse, and Pinot Noir. Fermented in concrete with 1 month of maceration of whole bunches, no pump-overs or punch-downs. 11% alcohol. Cime is the outline or shape of the mountain. Frisson is the “sensation of being on the crest,” according to Curtet. Score: between 9 and 9.5.

Unfortunately, these wines are not yet available in the United States, and earlier vintages are all but sold out. The US importer for Domaine Curtet is Martine’s Wines.