When I was first learning the little bit of Japanese that I speak, I was interested in adjectives. Maybe it’s the writer in me, but I always want to know how to describe something effectively. My explorations of Japanese gardens, temples, and the deeply aesthetic crafts of that culture all but required me to know how to describe something as beautiful. That Japanese word is kirei. You would use it to describe a flower, a painting, or your lover.

But there’s another word for beauty that is reserved for things that transcend normal beauty and touch something deeper in us. The best translation of utsukushii I ever heard was “sublime” but that only captures part of the soul-stirring, divine beauty that I’ve seen my Japanese friends trying to describe when explaining the word to me.

If you’re a wine lover, there’s one place in the world that captures this essence more than any other. For shorthand, I personally refer to it as the most beautiful vineyard in the world. I’d almost be prepared to defend that claim with my fists. But that doesn’t really do it justice. No, utsukushii seems to be about right for Rippon.

A Place of Refuge

When you ask Nick Mills to tell you the story of Rippon, he tells you the story of the place. He’s not likely to begin with his memories of growing up on the family farm. It takes him a while to get to the four generations of his family that have lived and worked on the edge of Wanaka Lake in the mountains of Central Otago. The establishment of Wanaka as sheep station in the mid-1860s isn’t far back enough, nor are the seasonal encampments of the native Maori people that once dotted the lakeshore. No, when Nick Mills talks about the land under his (usually bare) feet, he starts at the very beginning.

“If New Zealand came up out of the ocean, whatever came here had to fly or to swim,” he says. “Maybe we had two bats and a seal. But no grazing mammals. What we did end up having were big flightless chickens, and a lot of things happened out of that.”

Mills goes on to explain how predations by the native Moa helped many of the early plants of New Zealand to divaricate, or to form structures where their soft fleshy bits were on the inside, while their outsides got tough, stiff, and spiny. Many a bush-wacker in New Zealand has learned first-hand the uncomfortable results of divarication.

‘This is a hard land,’ says Mills. ‘A rough and tumble place that isn’t easy to live. There aren’t many carbohydrates, and there aren’t big animals to hunt.’ The implications for the native Maori being the absence of thick pelts to deal with the cold, and the need to have access to the coast to fish. Which means, mostly, they stayed out of the chilly mountains.

‘This,’ he says, sweeping his arm to take in one of the most stunning landscapes you’ll ever hope to see, ‘was summer camp. The Maori used to come up to these inland hinterlands to collect pounamu [greenstone] and hunt for game. The families would stay here by the lake, and while the men hunted, the women would teach their children hunting, fishing, and gathering. It’s a place of rest and education. Wanaka and wānanga have the same root: school, workshop, education.’

Mills is matter-of-fact as he goes on to describe the tumultuous history of the place his family calls home—the ambush and eating of the southern Maori by the northern island war chief Te Puoho, the retaliation and massacre by the southern tribes, the European settlement and parcellation of native lands—but eventually, he arrives at the point where most winemakers would begin their story: the 100 years that the Mills family has spent as farmers on this little patch of ground.

This telling of history, in a way, says almost everything you need to know about Nick Mills and the depth at which he feels his connection to the lakeside from which he coaxes some of New Zealand’s most profound wines. It’s an awareness of place that transcends the scale of human lifetimes, and an appreciation for everything that has gone into producing the soil he works, since the beginning of time.

“It’s a piece of land first. I see it as a unique individual. The craft is about the land,” he says. “It’s about looking after that land, which is what us humans have to stand behind right now.”

It’s also what humans literally have to stand upon. Mills once spoke perhaps one of the most profound narratives I’ve heard about wine a number of years ago at the New Zealand Pinot Noir event in Wellington, as he explained his understanding of the Maori term turangawaewae, which literally translates to “a place to put your feet,” but is infinitely more personal and complex, as you will appreciate if you click that link.

The Shaping of Rippon

The family farm gradually became the family vineyard, beginning in the 1970s.

“Dad went off to World War II in submarines,” says Mills. “He came back via Portugal. He saw schist in the Douro and when he came home, he noticed the resemblance and basically started planting everything he could find, even while people were telling him nothing would work. I remember taking cuttings during many of my school holidays.”

From the 25 varieties that Rolf “Tinker” Mills planted, roughly 80% on their own roots, six varieties ended up being the right ones for the sloping hills of decomposed schist kept just a little bit warm by the lake: Pinot Noir, Gamay, Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Sauvignon Blanc, and Osteiner. The latter is an exceedingly rare cross between Riesling and Sylvaner of which there are perhaps 2 hectares grown in the world, one of which is at Rippon.

When Nick and his wife Jo took over from his father in 2003, the vineyard already had nearly 30 years of dry-farmed, organic cultivation, without the use of pesticides, herbicides, or chemical fertilizers. The younger Mills immediately began the process of converting to biodynamics, which was accomplished in short order.

Apart from selecting the vines and maintaining the health of the soils, Mills tries to let the place shape the wines. He’s lucky enough to have been born someplace quite suited for it.

Lake Wanaka sits in a small basin within the Southern Alps mountain range in the center of New Zealand’s south island. The Central Otago wine region is the only part of the country that can be said to have a continental (as opposed to coastal) climate, with hot summers, cold winters, and a noticeable lack of rainfall. While the Roaring Forties (strong westerly weather fronts between the 40th and 50th southern parallels) bring massive amounts of rain to the western coast of New Zealand’s south island, the alpen rain shadow keeps most of that moisture from the interior.

The lake itself is a large thermal mass that further moderates the temperature, giving the plants just that little bit of extra warmth they need to avoid the hardest freezes of the winter. Consequently, there’s less diurnal shift than in other parts of Central Otago, and Mills says his grapes tend to ripen with lower potential alcohol than in other parts of Otago, and ultimately yield paler, less intensely pigmented wines.

The massive outcrops of decomposing schist provide a mineral-rich, inorganic substrate for the vine roots to explore, with shallow topsoils of glacial and alluvial origin adding yet more rock to the mix.

And then, of course, there’s the view. What vine wouldn’t thrive on that alone?

Listening For The Land’s Voice

Since taking over from his father in 2003, Mills has had a singular focus when it comes to winemaking: allowing the place he lives to express itself through wine.

As you might expect for a long-time biodynamic producer, nothing is added to Rippon wines save a small amount of sulfur. The grapes, if they are crushed, are crushed by foot, and the whites ferment in horizontal fermenters to maximize lees contact. There’s no temperature control.

In years when Mills believes the fruit from his oldest vines is totally pristine, he will make wines without any added sulfur at all, labeling those wines “Bequest.”

“Sometimes nature grants us the opportunity to make something special,” says Mills. “We’ve been bequeathed an opportunity, and we don’t take it for granted. The only way we’ll make a so-called ‘natural wine’ is if we can make a truly fine wine naturally. In 2013 and 2016 everything came together like that.”

Mills has strong feelings about winemaking, something he has long done intuitively, rather than by any standard formula. If the Gewürztraminer ferments finish early, he’ll sometimes throw the lees into the Riesling fermenter. He’s been known to take a hose to capture the carbon dioxide coming off one fermenter and then bubble it through another wine just beginning to ferment. To Mills, flavor is not nearly as important as texture.

“Fruit is what gets the bird to eat the seed. It’s what brings us to the wine, of course,” says Mills. “That’s important, but the truth of the fruit is the seed, the genetic material the vine can issue. The transmission to seed is very important, you might say it’s the whole purpose of terroir. You can’t really taste and smell a seed. But seeds make form and shape. I’m really driven much more by dry matter and texture and elasticity than I am by smells and flavors. This is what dry-farming, and own-rooted vines do—they drive energy into the skins and seeds of the grape.”

He continues, “For me wine is a digestive. It’s for the human body. Sure, aromatics and olfactory stimulus are brilliant, but that’s not so important. Keynotes, esters, aromatics, they aren’t the healthy stuff. Wine is a tonic. It’s something you’re giving to your body, it needs amino acids broken down to glutamates. When we first had wine, wine was a food. You bought it, drank it until it became vinegar, and then you used that too. I would rather have a wine that is about digestion than one that is about olfactory stimulus.”

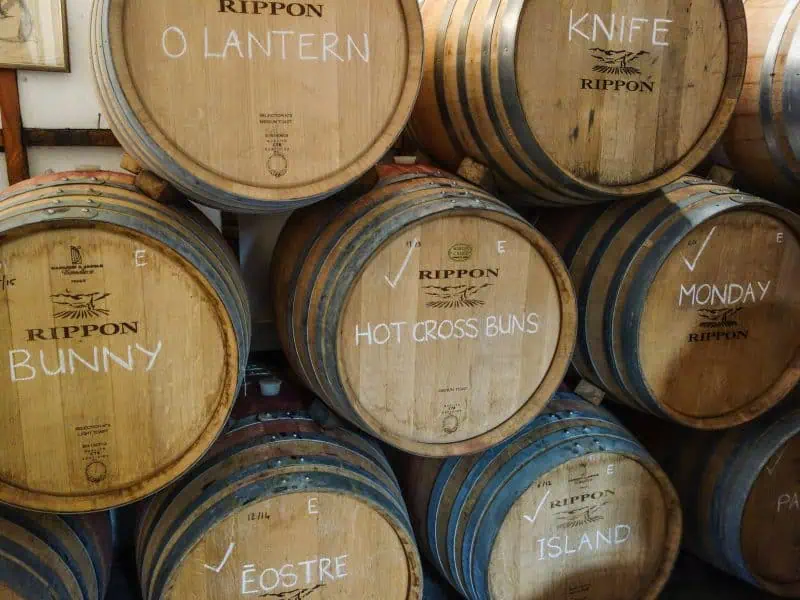

Mills makes his wines in a relatively compact, modest cellar that honestly isn’t much more than a shack. Separate blocks of the vineyard are picked and fermented separately. Each fermenter or batch of wine is given a name starting with a sequential letter of the alphabet, and then each barrel of wine from that fermenter gets a corresponding unique name, often a play on words. When I visited, the “Easter” fermenter had spawned barrels named “Bunny” and “Island” while the Jack fermenter begat “O Lantern” and “Knife.”

Most of the fruit from the main vineyard, Tinkers Field, gets blended together and simply becomes a Rippon “Mature Vine” wine, with the younger vines bottled separately under the moniker “Jeunesse.” A small block of the oldest vines is bottled separately as “Tinker’s Field” each year, as is another block known as “Emma’s Block,” after the Nick’s great-great-great grandmother, who was the first in the family to take the surname Mills.

More Than Beauty in a Bottle

I adore the wines of New Zealand, but Rippon’s wines hold a special place in my heart. I won’t demean the uniqueness of the place by trying to find some analogy to convey the special quality of the site that Mills has made his life’s work. There simply is no place like Rippon, and there are no other wines like Rippon in New Zealand, or the world.

This isn’t a revelatory statement. In the upper echelons of the wine world, it’s pretty well accepted that Rippon stands apart.

But that doesn’t mean Mills has an easy time selling his wines.

“It’s like we’re starting with a severe handicap,” muses Mills. “It makes me grumpy. I know where our wines sit in the context of the world. I’ve traveled, I’ve tasted, I’ve worked, and I know just how well these wines express their place. Yet somehow, in many places, we’re not taken as seriously as wines from the ‘Old World.’ I sometimes think it’s unfortunate that New Zealand has that word ‘New’ in it.”

Don’t get him started on geographic prejudice.

“Honestly, sometimes I have sommeliers tell me that they ‘don’t do southern hemisphere wines,’ as if it’s a real thing instead of some imaginary line humans invented. This craft [of wine] is universal, and my peers don’t have a country. We’re all just people who believe in growing the soil and guiding the living tissue of that soil into something we can taste or feel.”

When someone who appreciates the qualities of his wine still won’t buy it, Mills feels it like a gut-punch.

“This isn’t for me. It’s far beyond us. It’s not about building our brand. There’s greater things at stake here than whether people buy the wine or not. Rippon is a piece of land that is worth holding on to, worth protecting. It warrants the care we’re giving it over generations. But in order for people to look after a piece of land the market has to stand behind them. All that brand stuff is fine and good, but at a deeper level, this is about giving people the ability to make a living and stay on the land, to help it reach its potential through the culture that is developed on it.”

It’s not hard to sense the depth of Mills’ passion in the wines themselves. They are as honest as they are complex, seemingly unvarnished while also being incredibly refined. They don’t wear makeup because they don’t need any, lacking any pretensions towards perfection.

I’ve enoyed Rippon’s wines for years, but I hadn’t had older vintages until my visit, and they were frankly revelatory. These are wines that age incredibly well, blossoming into technicolor auroras of flavor and aroma, irrespective of Mills’ focus on texture. As if the beauty was there, just waiting to emerge.

“I’m just receiving the information we’ve been given by the land, and issuing it through a craft,” says Mills. “The place sends us in a certain way. For me, this is doing justice to the farm and to the place.”

If there were ever any wine that could do justice to the sublime beauty of a place, it’s a bottle of Rippon.

Tasting Notes

These wines are made in very small quantities, and not all wines make it to the US. Pretty much only the current release wines are findable online. I have provided links to buy where available. The wines are imported by Wine Dogs Imports.

2018 Rippon “Mature Vine” Riesling, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light straw-gold in color, this wine smells of tangerine zest and tangerine oil. In the mouth, pear and orange peel mix with a touch of baked apple and the sneaky brightness of grapefruit that emerges as the wine moves across the palate. Excellent acidity and distinctive character. 13% alcohol. Score: around 9. Cost: $32. click to buy.

2014 Rippon “Mature Vine” Riesling, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light blonde in color, this wine smells of mandarin zest, Asian pears, and honeysuckle. In the mouth, gorgeously stony flavors of wet chalkboard, pink grapefruit pith, and mandarin oranges have a bright honeysuckle sweetness as they head through a long finish. Stupendous acidity. 11% alcohol. Score: around 9. Cost: $32.

2013 Rippon “Mature Vine” Riesling, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Pale blonde in color, this wine smells of mandarin zest and a hint of paraffin and Asian pear. In the mouth, delicate flavors of mandarin zest and lemon pith mix with crushed stone. Softer acidity than the ’14 vintage, with a beautiful liquid stone quality. 11.5% alcohol. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $32.

2019 Rippon Gewurztraminer, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Pale straw in color, this wine smells of orange peel and unripe peaches. In the mouth, crisp orange peel, citrus pith, and faint peachy and lychee flavors are backed by stony brightness and good acidity. There’s a light tannic chalkiness to the texture. Lean for the variety, and quite easy to drink. 13% alcohol. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $32. click to buy.

2016 Rippon Gewurztraminer, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Near colorless in the glass, this wine smells of wet chalkboard and dried orange peel. In the mouth, crushed stone, orange peel, and a hint of lychee are welded to a chalky, tannic backbone. Good bright acidity. Score: between 8.5 and 9. Cost: $32.

2016 Rippon Osteiner, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Palest gold in the glass, this wine smells of wet chalkboard, Asian pear, and white flowers. In the mouth, a bright lemony explosion in the mouth gushes with pink grapefruit and lemon juice. Fantastic brightness and juiciness. Love it. 23-year-old, own-rooted, dry-farmed vines of the variety known as Osteiner, which is a cross between Riesling and Sylvaner. 11.9% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $32.

2017 Rippon “Mature Vine” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Medium ruby in the glass, this wine smells of dried herbs and raspberry fruit. In the mouth, dried herbs and flowers mix with raspberry and redcurrant flavors shot through with a touch of cedar. Earthier notes add a dusty quality, while the faintest of gauzy tannins caress the mouth. Fantastic acidity leaves a wonderful citrusy brightness in the finish along with a hint of dusty earth. 13% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $65. click to buy.

2013 Rippon “Mature Vine” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light to medium garnet in the glass, this wine smells of wet earth and forest berries. In the mouth, gorgeous savory cherry and raspberry flavors are shot through with a hint of citrus peel. Fantastic acidity keeps the wine lush and fresh across the palate, emphasizing the wet-chalkboard minerality and letting the berry, herb, and floral notes soar for a long time in the finish. Powdery tannins, beautifully fine. 13% alcohol. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $90.

2012 Rippon “Mature Vine” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light garnet in color, this wine smells of dried flowers and raspberries and forest floor. In the mouth, juicy, bright raspberry and redcurrant flavors have a deep crushed stone and forest floor backbone. Powdery tannins billow around the edges of the mouth as the fantastic acidity makes the wine dance across the palate. Lovely dried herb and citrus peel notes linger in the finish along with that pulverized rock that is so enthralling. 13.5% alcohol. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $90.

2010 Rippon “Mature Vine” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Medium garnet in the glass, this wine smells of fantastically perfumed dried flowers, forest floor, and crushed mixed berries. In the mouth, juicy mulberry and black raspberry fruit seems strained through crystalline quartz (or schist as the case may be) as it soars through an incredibly perfumed finish. Deeply mineral, with fantastic acidity and muscular tannins that are starting to lounge their way into a beautiful structural support for the fruit. Hints of dried herbs linger in the finish with citric notes. Stunning. Score: between 9.5 and 10. Cost: $90.

2008 Rippon “Mature Vine” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light to medium ruby in the glass with still a hint of purple, this wine smells of red apple skin, raisins, dried cherries, and forest floor. In the mouth, sweet raspberry and cherry fruit mix with cedar, nutmeg, and dried red apple skin for a beautifully mouthwatering mélange of fruit and spice and earth. Is this wine at its peak? I don’t know. But I love the heights it takes me to. Utterly compelling, complex, and commanding attention. 13.5% alcohol. (Tasted out of 375ml) Score: between 9.5 and 10. Cost: $90.

2013 Rippon “Emma’s Block” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light to medium garnet in color, this wine smells of dried herbs, dried flowers, and forest berries. In the mouth, gorgeous wet-chalkboard minerality underlies pure and clear flavors of raspberry, mulberry, and redcurrant. Dried flowers and herbs soar through the finish while powdery tannins grip the edges of the mouth. Fantastic length. Amazing acidity. Score: around 9.5. Cost: $100.

2013 Rippon “Tinker’s Field” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Medium garnet in color, this wine smells of forest floor and berries. In the mouth, very tightly wound flavors of black raspberry and raspberry leaf have a muscular tannic structure to them that speaks of the need for time to mature in the bottle. Excellent acidity and length with notes of green herbs lingering in the finish with a deep pure wet pavement minerality. 13.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $100.

2013 Rippon “Tinker’s Bequest” Pinot Noir, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Medium garnet in the glass, this wine smells of rich forest berries and deep loam. In the mouth, gorgeously bright and pure mulberry and cranberry flavors seem strained through powdered rock. There’s definitely a hint of the carbonic grapeyness you’d find in Beaujolais, but with the depth and complexity of Pinot fruit. Fine-grained muscular tannins persist for a long time in the finish. 13.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $120.

2015 Rippon Gamay, Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand

Light to medium garnet in the glass, this wine smells of bright mulberry and cherry fruit. In the mouth, stony flavors of mulberry and cherry, and strawberry have a wonderful fine powdery tannic skein to them and bright juicy core thanks to excellent acidity. Incredibly easy to drink and beautifully balanced. 28-year-old vines – 12 rows in Tinker’s Field – somewhere between 30 and 80 cases made each year. 12.5% alcohol. Score: between 9 and 9.5. Cost: $60.