One year ago, we launched the Old Vine Registry, the world’s first and most comprehensive global database of old-vine vineyards around the world. We launched with around 2200 vineyards from 29 different countries. Today, one year later, our entries have grown more than 50% to a total of 3353 vineyards across 36 different countries.

As a crowd-sourced, non-profit public database, the addition of those 1100 new vineyards has come from the contributions of more than 200 individuals and several organizations around the world. We’ve also received a whole raft of corrections to the existing data in the database, also very welcome.

If you’re interested, you can watch the recording of our anniversary webinar here.

Good progress aside, we’re barely scratching the surface of the old vine world.

10,000 Vineyards in 3 Years

Take a look at the paltry registration coverage we have in certain regions within the Old Vine Registry:

Rioja: 7 vineyards

Chateauneuf-du-Pape: 7 vineyards

Beaujolais: 14 vineyards

Chablis: 0 vineyards

Chianti: 5 vineyards

Etna: 21 vineyards

Campania: 7 vineyards

Tokaj: 5 vineyards

Cornas: 1 vineyard

Santorini: 2 vineyards

Lebanon: 1 vineyard

Switzerland: 2 vineyards

Faugères: 3 vineyards

Loire Valley: 15 vineyards

Champagne: 8 vineyards

Canada: 19 vineyards

Bierzo: 1 vineyard

Austria: 7 vineyards

Each of the regions above has hundreds and in some cases, thousands of old-vine vineyards.

Additionally, we have zero vineyards registered from anywhere in Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Cape Verde, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Malta, Morocco, Poland, Tunisia, Ukraine, and Slovakia. All of these countries no doubt have old vines worth keeping track of.

In short, we’ve got a ton of work to do if we ever want this database to be even partially representative of the global old-vine landscape.

With that in mind, we’ve set a BHAG (Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal) to register 10,000 vineyards in the next 3 years.

To encourage the old vine equivalent(s) of Stephen Pruitt (the single individual responsible for more than 1/3 of the content on Wikipedia) to step forward and help us out, we’ve launched the Heritage Vine Hunt Contest.

The Heritage Vine Hunt

The contest will run for three years, with three winners declared at the end of year one, three at the end of year two, and one grand prize winner at the end of the third year.

The grand prize is a free trip (airfare, meals, tickets) to an Old Vine Conference field trip somewhere in the world, a prize that, depending on where you live, could be worth more than $2000.

In addition to fabulous prizes, winners will get some serious bragging rights, not to mention quite a lot of social media coverage as we sing their praises.

Entering the contest is as simple as submitting new (not yet registered) vineyards to the Old Vine Registry, which can be done using the web form or (more easily) by e-mailing the data-entry spreadsheet (import into Google Sheets if you don’t do Excel) to oldvineregistry@gmail.com.

Competition Strategies

So, you want to compete, but you’re not sure how to get started? I’m more than happy to help. Feel free to send me an e-mail and I’ll set you loose on any number of little projects that will yield a bunch of old vineyards.

More broadly, here are a few key strategies for anyone who wants to spend some spare time ferreting out old-vine vineyards.

1. Sifting through Cellartracker

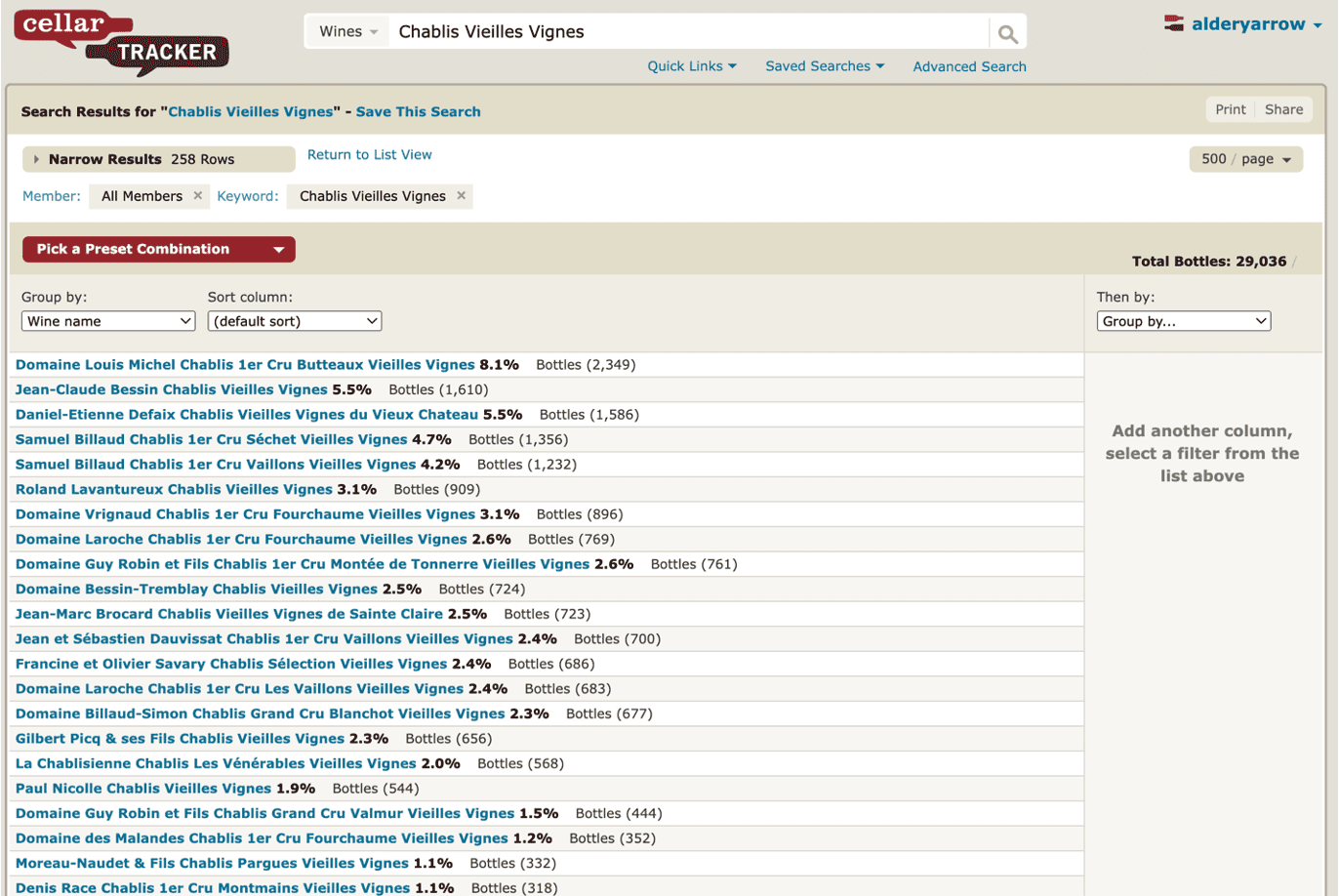

Cellatracker has one of the largest and most complete publicly available databases of wine in the world. If you were to go onto Cellartracker and search for “Chablis Vieilles Vignes” and then use the “summarize by” controls to summarize the results by “individual wine,” you will produce a list of 258 Chablis wines that have Vieilles Vignes in their names:

Then you just Google the websites of the producers and see if they have information on the size and planting date for that vineyard, and violà you’ve got an entry for the Old Vine Registry. Lather, rinse, repeat. You can do this with every appellation in the world and the many variations of old vine, vigna vecchia, alte reben, vinas viejas, vinhas velhas, etc. in the appropriate language of origin.

2. Approach regional wine authorities or local experts

Most appellations in the world have a regional marketing organization responsible for the promotion of that appellation. Our little volunteer team (OK, mostly me) hasn’t had the time to approach the hundreds of such organizations around the world and ask them if they might have records about the planting dates of their vineyards. We’ve been lucky enough to get some proactive outreach from folks in Moldova, Armenia, the Douro, and a few others, but there are literally hundreds more groups that may well have a spreadsheet waiting to hand you with this information, especially if you speak their native tongue and know how to ask the right person and do it nicely. If you need suggestions or help figuring out how to get in touch with such organizations, let me know.

3. Search government records

Many governments have departments of agriculture that carefully track the vineyards in the entire country, or within a given region. Just as an example, I happen to know that every winegrower in Beaujolais is required by law to register (and have on hand in case an inspector comes calling) a form about each vineyard they own, indicating the planting date, acreage, and varieties planted in that vineyard. I know this because one of them showed me their records. What I don’t know, because I don’t speak French and don’t know where to begin, is what government agency has ALL such records and how you would get ahold of the entire database if you wanted. But someone with fluent French and some decent research skills should, it seems to me, be able to unearth this data.

Still other governments may already make such information available online in their native language, if you only know how and where to look.

4. The old fashioned way

Choose a wine region that you know has a lot of old-vine plantings, find a list of all the producers in that region, and start making phone calls (e-mails, in my experience, don’t work). Tell them you’re doing research for a non-profit organization focused on promoting old-vine vineyards and ask whether they have any vineyards older than 35 years that could be added to the Old Vine Registry.

Tips for Contestants

Regardless of how you choose to compete, here are a few key tips to make sure that you are successful and that the data we get for the Old Vine Registry is accurate and complete.

- Only vineyards 35 years old or older (planted in or before 1989) qualify for inclusion

- We are interested in living vineyards—the vines in the ground right now have to be old—a vineyard first established in 1895 but then replanted in 2002 doesn’t count

- Search the database to make sure we don’t already have the vineyard registered before submitting a vineyard entry

- Dating a vineyard isn’t an exact science and isn’t always easy; we allow for estimated dates in our submission process; just make sure you’re getting an estimate from the person who owns the vineyard, not making one up yourself

- Our general approach is to consolidate vineyard listings; the only reason to break up a contiguous vineyard into separate blocks (regardless of how a producer refers to their vineyard) is if the blocks have significantly different planting dates; two blocks that took two years to complete planting should likely be considered a single vineyard with an estimated planting date

- Please participate in good faith and submit real data that is as accurate as you can make it; definitely don’t fabricate data; we’ll be verifying every vineyard record submitted

- The minimum information we need about a vineyard is its location, the date it was planted, the grape varieties in it, and its size. We also really prefer to have the name of the owner or the primary winery producing grapes from the vineyard, though in some cases this may be unknown, or in very rare cases, withheld if the owner has privacy concerns

If you have any questions you’re welcome to reach out to me at any time.

Happy Hunting!